|

|  Manatees

The West Indian (Trichechus

manatus), lives in the warm coastal

waters of the southern United States,

Mexico, the Caribbean Islands, Central

America (including Belize), and the

northeastern countries of South

Modern relatives of Sirenians are elephants,

aardvarks, and hyraxes, which

are small rodent-like mammals. The

scientific genus name “trichechus” is

Latin for hair and refers to the small

hairs that are found all over the

manatee’s body. The name Sirenian

comes from a word in ancient mythology

known as “siren”. Sirens were halfwoman-

half-bird creatures known to

lure sailors to dangerous parts of the sea

and their deaths. In Homer’s “Odyssey”,

sirens were mythical women who

lured the men into a dangerous whirlpool.

Manatees range in color from gray

to brown with wrinkled skin and single

bristle-like hairs scattered all over their

bodies. They have thick whiskers that

cover their snouts and their upper lip is

divided into halves, which close like pliers

on the plants they eat. Despite their

small eyes and lack of outer ears, manatees

are thought to see and hear quite

well. The nostrils are located on the

topside of the snout and can be closed

tightly by valves when the manatee is

underwater. Their eyes have inner

membranes that can cover the eyeballs

for additional protection. Manatees have

a paddle-shaped tail that is pumped up

and down to move them along and propel

their bodies through the water. They

also have two flippers in the front of their

bodies that they use for guiding their

bodies and scooping up their food. Some

manatees have three or four nails on the

tip of each flipper. The average adult

manatee weighs 1,500 to 1,800 pounds

and measures ten to twelve feet in

length. Adult females are generally

larger than adult males.

“Sea cow” is a common term used for both manatees and dugongs, and the name likely comes from the fact that manatees are herbivores and spend most of the day grazing like cows that spend most of their day grazing on grass and hay. Manatees can consume more than 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of plants in a day and typically eat four to nine percent of their body weight in food. Manatees have been known to eat over sixty species of plants with the most common being sea grass. They have a flexible upper lip that they use to bring food into their mouth. They do this by grabbing and tearing the plant with their lips. The snout of West Indian manatee is bent further down than other species in this family and enables them to feed mainly on sea grasses growing on the sea floor. Because sand is commonly mixed with the plants their teeth are easily ground down so their teeth are continuously being replaced. Manatees mostly eat in the water but they use high tides to reach feeding grounds and shoreline vegetation that are inaccessible at low tides.

Amazingly, they are able to crawl part

way onto a bank to reach shoreline vegetation.

An average manatee spends six to

eight hours a day feeding, two to twelve

hours sleeping, and the rest of the time

traveling. When resting, a manatee is

able to suspend itself near the surface

of the water but it can also lie on the

bottom of the sea floor. A large resting

manatee can stay submerged for about

twenty minutes, but others need to resurface

every three to four minutes.

When manatees are using a great deal of energy, they may surface to breathe as often as every 30 seconds. Well known for their gentle, slow-moving nature, manatees have also been known to body surf or barrel roll when playing. By using both their tail and flippers, manatees are capable of complex maneuvering including somersaults, rolls, and swimming upside-down. A manatee typically swims with up-and-down motions of its body and tail, like a whale or dolphin. Although manatees typically swim at a speed of two to six miles per hour, they have been known to be able to sprint at speeds of up to fifteen miles per hour.

Manatees use various forms of communication

in the water such as sound,

sight, taste and touch. Manatees have

an acute ability to hear and squeals are

often used to keep contact between a

mother and calf. It is thought that manatees

are able to hear sounds that are even

too low for humans to detect. However,

vision seems to be the preferred method

of navigation. Sometimes though, they

are unable to see through some of the

murky waters of their habitat. Individuals

rub themselves against hard surfaces

which may be a way that they clean

themselves, but this behavior may also

be a way that manatees leave their scent

so other manatees can find them.

The reproductive rate for manatees

is slow. Female manatees are not sexually

mature until five years old, and

males are mature around nine years of

age. Typically, gestation periods for

West Indian manatees range from

twelve to fourteen months. Calves are

born weighing between 60 and 70 pounds

and measuring about three to four feet.

The normal interval between births is

two to five years and mothers nurse their

young for a long period. The calf may

remain dependent on its mother for up

to three years.

Historically, manatees of Belize have been hunted for food, their hides, and their bones. This hunting continues in many South and Central American countries. In Guyana, a country in northeastern South America, people have used manatees to keep waterways free of weeds. West Indian manatees have no natural enemies, and it is believed they can live 60 years or more. Many manatee mortalities are human-related and occur from collisions with watercraft. Most manatees have a pattern of scars on their backs or tails from collisions with boats. Scientists use these patterns to identify individuals, but these collisions can be fatal for the manatee. Besides boating accidents, manatees have been found crushed or drowned in flood-control gates and also suffer from pollution, ingestion of fish hooks, litter and monofilament line; entanglement in crab trap lines and vandalism. Ultimately, however, loss of habitat is the most serious threat facing manatees today. West Indian manatees in the United States are protected under federal law by the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which make it illegal to harass, hunt, capture, or kill any marine mammal. They are all listed as vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN’s (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) red list. The order once included a fifth modern species, the Steller’s sea cow. Unfortunately, the Steller’s sea cow is now extinct due to over hunting. Manatees living in the Belizean coastal waters are not as affected by human activity as they are in other locations such as Florida. Although the manatees of Belize are not as affected by water craft traffic now, it may become a danger as population and development in Belize increases. The Antillean Manatee is listed as endangered under Belize’s Wildlife Protection Act of 1981.

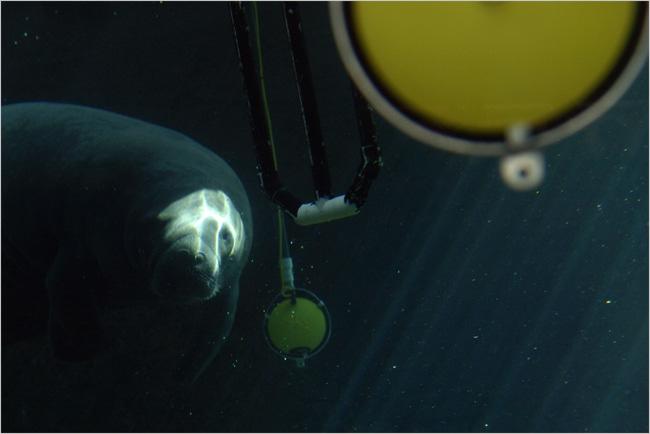

For those of us who cannot resist the magnetism of creatures large and small, manatees can trigger the same passion and excitement as seeing panda bears and wide-eyed baby seals. Perhaps it is their human like faces and behavior that attract us to these gentle mammals and takes a hold of our hearts. What ever it is, there is no denying the anticipation and excitement one feels when entering the Swallow Caye Wildlife Sanctuary. Here Willy orders the boat engines to be turned off and moves to the bow where he begins using a very long, sturdy stick to “pole’ the boat quietly through the calm waters that surround the mangrove caye. Today the winds are stronger than usual and the ordinarily clear water is a bit murky. Willy can spot where the manatees are burrowing into the sandy sea bottom and the pieces of floating sea grass in the water indicate that they are feeding near by. As we all stand and look with shielded eyes we can see the tip of their noses as they surface for air, and one visibly spouts water. Unfortunately the creatures are more content to lay low and Willy decides that we will go on to Goff Caye for lunch and snorkeling, and will return later in the afternoon for another look.

We return to the island, where lunch and our other boat mates await us. Over barbequed chicken, curried potatoes, fresh fruit, veggie salad, incredible brownies and a cold Belikin beer we all visit with our new acquaintances and enjoy the fabulous meal. With full tummies and new energy, we again board the boat and head back to Swallow Caye in search of the elusive manatee.

We headed back to Ambergris Caye around 4:30 pm and enjoy Rum Punch and good company while watching the sun set in a tangerine and crimson painted sky. For most of us we know what a rare and special experience our day has been, and we will forever remember the day that we shared with the manatees and the precious creatures of the Caribbean Sea.

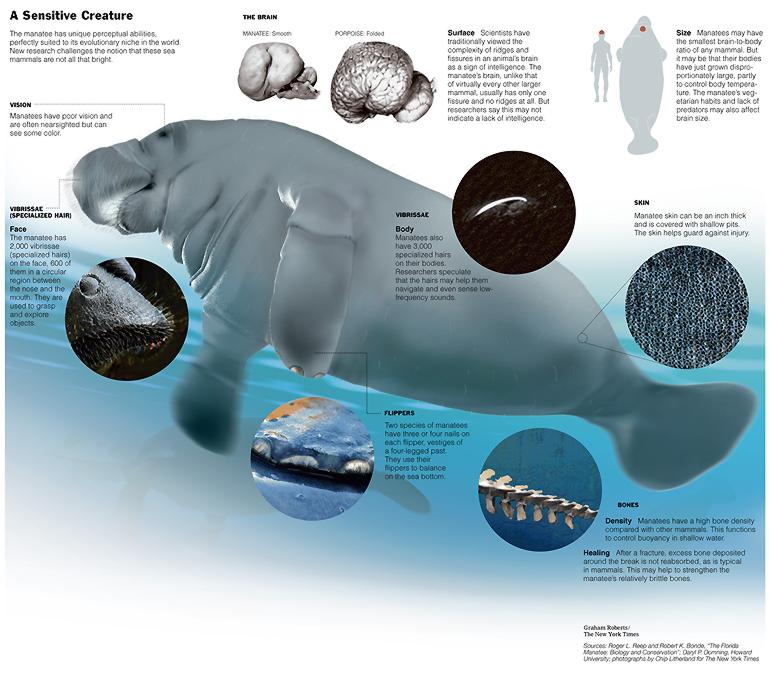

New York TImes It is a good thing the manatee has thick skin. To the dolphins, the whales, the sea otters go the admiring oohs and ahs, the cries of, “How sleek!” “How beautiful!”

Cleverness is unhesitatingly ascribed to the dolphin. But the manatee is not seen leaping through hoops or performing somersaults on command, and even scientists have suspected it may not be the smartest mammal in the sea. Writing in 1902, a British anatomist, Grafton Elliot Smith, groused that manatee brains — tiny in proportion to the animals’ bodies and smooth as a baby’s cheek — resembled “the brains of idiots.” Yet the conception of the simple sea cow is being turned on its head by the recent work of Roger L. Reep, a neuroscientist at the University of Florida at Gainesville, and a small group of other manatee researchers, including Gordon B. Bauer, a professor of psychology at New College of Florida, and David Mann, a biologist at the University of South Florida. In studies over the last decade, they have shown that the endangered Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) is as unusual in its physiology, sensory capabilities and brain organization as in its external appearance. Far from being slow learners, manatees, it turns out, are as adept at experimental tasks as dolphins, though they are slower-moving and, having no taste for fish, more difficult to motivate. They have a highly developed sense of touch, mediated by thick hairs called vibrissae that adorn not just the face, as in other mammals, but the entire body, according to the researchers’ recent work. And where earlier scientists saw in the manatee’s brain the evidence of deficient intelligence, Dr. Reep sees evolution’s shaping of an animal perfectly adapted to its environment. Dr. Reep — a co-author, with Robert K. Bonde, a biologist at the Sirenia Project of the United States Geological Survey, of a recently published book, “The Florida Manatee: Biology and Conservation” (University Press of Florida) — argues that the small size of the manatee brain may have little or nothing to do with its intelligence. Brain size has been linked by some biologists with the elaborateness of the survival strategies an animal must develop to find food and avoid predators. Manatees have the lowest brain-to-body ratio of any mammal. But, as Dr. Reep noted, they are aquatic herbivores, subsisting on sea grass and other vegetation, with no need to catch prey. And with the exception of powerboats piloted by speed-happy Floridians, which kill about 80 manatees a year and maim dozens more, they have no predators.

But he also suspects that rather than the manatee’s brain being unusually small for its body, the situation may be the other way around: that its body, for sound evolutionary reasons, has grown unusually large in proportion to its brain. A large body makes it easier to keep warm in the water — essential for a mammal, like the manatee, with a glacially slow metabolism. It also provides room for the large digestive system necessary to process giant quantities of low-protein, low-calorie food. The manatee must consume 10 percent of its 800-pound to 1,200-pound body weight daily. Hugh, 22, and Buffett, 19, captive manatees at the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Fla., are fed 72 heads of lettuce and 12 bunches of kale a day, their trainers say. And in a 2000 study, Iske Larkin, a researcher in Dr. Reep’s laboratory, used colored kernels of corn to determine that food took an average of seven days to pass through a captive manatee’s intestinal tract — a leisurely digestive pace comparable to that of a koala or a two-toed sloth. The smooth surface of the manatee’s brain — it generally has only one main vertical fissure, or sulcus, and no surface ridges to speak of — is more puzzling, Dr. Reep concedes. The brains of virtually every other mammal bigger than a small rodent show some degree of folding. And scientists have generally taken the human cortex, a study in ridges and crevasses, as a model of higher-order mental process, assuming accordingly that brain convolution is a sign of intelligence. “I would make a guess that if you showed a manatee brain to a modern neuroscientist, to this day, most would consider that the manatee is not very smart, that idea is so ingrained,” Dr. Reep said.

But he added that scientists still know almost nothing about what drives the development of brain formation. Evolutionary lineage appears to have an influence. The brains of primates tend to have different patterns of convolution than those of carnivores, for example. And mechanical factors like brain size and the denseness of neural tissue in the cortex may play a role.

In any case, he said, brain convolution “doesn’t seem to be correlated with the capacity to do things.” More to the point, intelligence — in animals or in humans — is hard to define, much less compare between species, Dr. Reep said. Is the intelligence of a gifted concert pianist the same as that of a math whiz? Is a lion’s cunning the same as the cleverness of a Norwegian rat? The manatee is good at what it needs to be good at. Sirenia, a biological order that includes the dugong and three extant species of manatees, appear in the fossil record in the early to middle Eocene, about 50 million years ago, around the same time as whales, horses and other mammals, said Daryl P. Domning, a professor of anatomy at Howard University who has collected and studied the fossils of manatees and other sirenians around the world. Four-legged land mammals that returned to the sea, the sirenians shed their hind legs but retained vestigial pelvic bones and, in two manatee species, nails on their flippers. Manatees count among their close relatives the elephant and the rock hyrax. Another sirenian, Steller’s sea cow, lived in the Bering Sea and exceeded 5,000 pounds. It was hunted into extinction in the 1700’s. Although dugongs appear in the folklore of Palau, sirenians in general “don’t seem to have inspired the amount of awe that other animals did, like pumas and jaguars and things like that,” Dr. Domning said. “You don’t find them putting up monuments or statues to them.” Florida manatees, a subspecies of the West Indian manatee, thrive in warm, shallow coastal waters and migrate when the temperature drops. They spend a great deal of time eating, with frequent naps between meals. Their social world is relatively straightforward. Males mate with females in a violent affair that resembles a gang rape; manatee calves stick close to their mothers for about two years, then head off on their own. Groups of manatees may cluster, playing, grazing and dozing at a warm-water source — a power plant, for example. But they are just as likely to be loners, striking out wherever the warm currents take them, even if that means passing the Statue of Liberty and heading up the East River to Rhode Island, as an earlier northward manatee pioneer, Chessie, did in 1995. (The manatee spotted in the Hudson in early August was seen on Aug. 17 even farther north, off Cape Cod. But two days later it had turned south again to Rhode Island. The last reported sighting was the afternoon of Aug. 25, in Bristol Harbor, R.I. ) The manatee’s sensory capacities and brain organization, researchers are learning, are perfectly suited to its style of life. In the dim, muddy shallows where manatees feed, for example, sharp eyes are less than useful. And sight is not a manatee’s strong suit, though the heavy-lidded wrinkled dimples that serve as eyes are undoubtedly part of the animal’s charm. Manatees distinguish colors. The orange of carrots in a trainer’s hand can inspire a captive manatee to an uncharacteristic speed. But they are bad at distinguishing brightness, and they are clumsy, frequently bumping into things. In 2003, Dr. Bauer and four colleagues, including Debborah Colbert and Joseph Gaspard III of the Mote Marine Laboratory, reported in The International Journal of Comparative Psychology on the visual testing of the Mote manatees, Hugh and Buffett. The manatees were trained to discriminate between two underwater panels of evenly spaced vertical lines, swimming toward the correct panel for a reward of apples, beets, carrots and monkey biscuits. By varying the distance between the lines, the researchers showed that Buffett’s eyesight was about 20/420, similar to a cow’s and far worse than a human’s. Poor Hugh, Dr. Bauer said, was blind “even by manatee standards.” Yet far more valuable than sight in murky water is an acute sense of touch, and it is here that manatees excel. Their mastery of the tactile world, Dr. Reep and his colleagues have recently established, comes from the thick, bristly hairs called vibrissae. Unlike normal hair fibers, each vibrissa is a finely calibrated sensory device, its follicle surrounded by a blood-filled pocket or blood sinus. The movement of the hair produces changes in the fluid that are registered by receptors around the hair follicle, which transmit the information to the brain via hundreds of nerve fibers. An increase in blood pressure increases the sensitivity of the hairs. In research over the last five years, Dr. Reep and his colleagues have shown that manatees have 2,000 facial vibrissae of varying thickness, 600 of them in the so-called oral disk, a circular region between mouth and nose that the manatee uses much like an elephant’s trunk, to grasp or explore objects. Each facial vibrissa is linked with 50 to 200 nerve fibers. An additional 3,000 vibrissae are spaced less densely over the rest of the body. Rats, dogs, sea lions and other whiskered animals also have vibrissae, but not in such large numbers and typically only on the face. In research not yet published, Diana Sarko, a graduate student in Dr. Reep’s lab, confirmed that another mammal has vibrissae dispersed over its body, the rodent-faced, rabbit-size rock hyrax, the manatee’s distant cousin. Like the manatee, the hyrax, which inhabits rocky outcroppings, spends much of its time in dim light and has poor vision. “Rock hyraxes live in little cave dwellings, so they probably use these hairs to navigate in these dark surroundings,” Ms. Sarko said. In testing, Buffett, Hugh and other captive animals have proved just how acute a manatee’s tactile sense can be. Using the bristles on the oral disk and the upper lips, manatees can detect minute differences in the width of grooves and ridges on an underwater panel. A manatee tested by a team of researchers in Germany could distinguish differences as small as 0.05 millimeters, as well as an elephant performing the same task with its trunk, and almost as well as a human. Hugh and Buffett did even better, outperforming the elephant and, in Buffett’s case, the human. The findings were presented at the 16th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals in 2005. A sensory modality that is so important should be prominently represented in the brain. And, confirming an observation first made by a German scientist in 1912, Dr. Reep’s research team has identified large clusters of cells called Rindenkerne in sensory processing areas in the deep layers of the manatee’s cerebral cortex. These clusters, the researchers suspect, are the manatee equivalents of the cell groupings called barrels found in other whiskered species like mice and rats, regions that process sensory information from the vibrissae. Even more tantalizing is that, in the manatee, these clusters extend into a region of the brain believed to be centrally involved with sound perception. “Either these things have nothing to do with the hair at all, or the more exciting possibility is that perhaps somatic sensation is so important that the specialized structure is overlapping with processing going on in auditory areas,” Dr. Reep said. The normal hearing of manatees is known to be quite good in certain ranges, better than that of humans. In studies published in 1999 and 2000, Edmund and Laura Gerstein of Florida Atlantic University found that the underwater hearing of two captive manatees in a pool was sharpest at high frequencies — in the 16-to-18-kilohertz range — findings that have complicated the debate about powerboats. Though Florida has spent years trying to persuade boaters to slow down in areas that manatees frequent, the high frequencies emitted by a boat moving at high speed may be easier for the animals to hear (although having the time to get out of the way is a different matter). But in a study also presented at the marine mammal meetings, Dr. Bauer, Dr. Reep and colleagues have found hints that manatees can also “hear” low-frequency sounds, perhaps by using the vibrissae on their bodies to detect subtle changes in water movement. Hugh and Buffett were able to determine the location of three-second low-frequency vibrations in the 23-to-1,000-hertz range with up to 100 percent accuracy. The researchers plan to repeat these experiments with the vibrissae covered, to see whether the manatees still score highly. If they do, it will suggest that they have a capacity unique among mammals and may help biologists explain, among other things, how they navigate back to their favorite patches of sea grass each year and how they monitor the movements of other manatees in cloudy water. Fish and some amphibians have similar sensory systems, mediated by cells running down the sides of their bodies. Called the lateral line, this system is “the reason why we can sneak up behind a fish but cannot grab it,” Dr. Reep writes. For now, the question of how intertwined the sensory abilities of manatees might be remains unanswered. Yet even what is known reveals a degree of complexity that argues against labeling them as sweet but dumb — peaceable simpletons. Dr. Domning of Howard could not agree more. “They’re too smart to jump through hoops the way those dumb dolphins do,” he said. Click here for an Audio Slide Show: The Mind of the Manatee . Fascinating pics and audio descriptions of their skin,hairs, noses, lips, hear their voices.... really cool.

Click picture for larger version

Rare Belize Manatee Sighting Caught on Video at Blackbird Resort

Belize is home to a sub-species of the West Indian manatee, one of four living species of manatees. The other three are the West African manatee, the Amazonian manatee and the dugong. The West Indian manatee is divided into two species, Florida & Antillean. Manatees thrive in warm waters due to its slow metabolism. Because of year-round Caribbean waters, the Antillean manatee does not need to migrate as the Floridian manatee does when the temperature drops below 86 degrees. In the US, West Indian manatees are protected under federal law by the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The Florida species specifically have suffered human-related injury or death due to pollution, boating accidents and ingestion of fish hooks, litter and monofilament line. The Antillean manatee found in Belize has suffered less due to lesser population of watercraft, however, it is listed as endangered under Belize’s Wildlife Protection Act of 1981. An adult manatee averages 10 feet in length and weighs between 800-1200 pounds. These slow-moving, gentle creatures spend their time eating, traveling or resting in shallow waters. Manatees are herbivores; munching on seagrass and other plant life, resembling cows that graze for much of the day on land, bestowing upon them the nickname “sea cow”. Since manatees are mammals they must surface for air. When exerting energy eating or playing, this could be as often as every 30 seconds, or when resting they can remain submerged for up to 20 minutes.

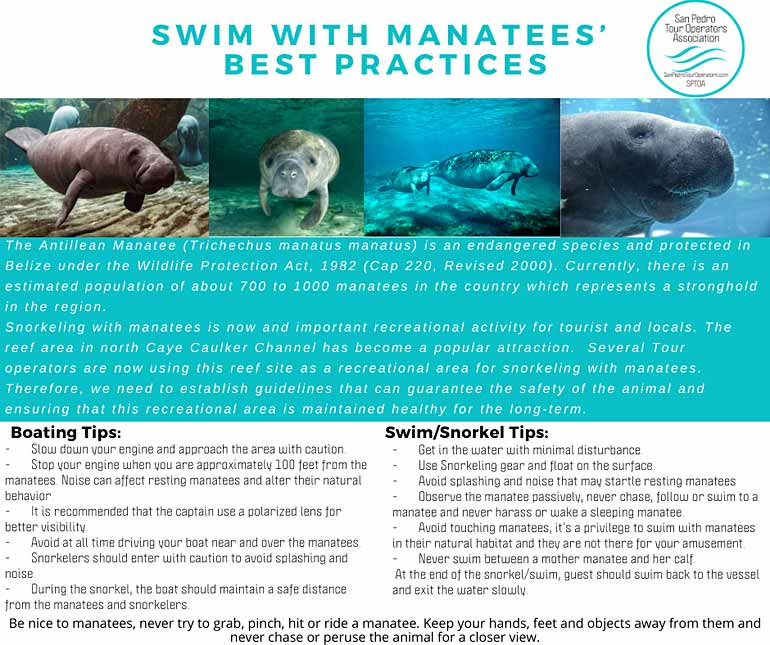

Having no known natural enemies, they may live as long as 60 years and generally travel solo. Females mature at around five years and give birth every two to five years to usually one calf, who is born measuring two to four feet and weighing between 6o-70 pounds. They stay with mommy up to three years before moving on their own. In the past, manatees were often mistaken for mermaids by the first Europeans to discover them. However, upon getting a closer look, they were disappointed to discover they were not quite the alluring, mysterious half-woman, half-fish creatures of mythical fairytales. Seeing and filming one of these intriguing creatures is a rare treat and our very own Divemaster Cardinal, who has been with us for over 5 years, has never spotted one. Many thanks to our guest Dave Runnalls who was able to capture this amazing footage last week during a dive trip to the Great Blue Hole! Please enjoy our video and be sure to learn more about the Belizean manatee by visiting Wildtracks, a non-profit organization formed in 1996 dedicated to “Conservation, Education & Research.” Swim with Manatees' Best PracticesThe Antillean Manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) is an endangered species and protected in Belize under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1982 (Cap 220, Revised 2000). Currently, there is an estimated population of about 700 to 1000 manatees in the country which represents a stronghold in the region. Snorkeling with manatees is now and important recreational activity for tourist and locals. The reef area in north Cave Caulker Channel has become a popular attraction. Several Tour operators are now using this reef site as a recreational area for snorkeling with manatees. Therefore, we need to establish guidelines that can guarantee the safety of the animal and ensuring that this recreational area is maintained healthy for the long-term.

Related Links: Click here to return to the main page for Caribbean Critters

|

Manatees pronounced “MAN uh

TEES”, have been called many names,

including sirenians, sea cows and even

mermaids. The first Europeans to encounter

manatees thought that they were

seeing the mythically beautiful mermaids,

which were believed to be half

woman, half fish creatures. On closer

inspection however, they were disappointed

to see that these animals were

not quite as beautiful as they thought.

Manatees and dugongs are members

of the order Sirenia. Sirenians include

four living species: the West Indian

manatee, the West African manatee, the

Amazonian manatee, and the dugong.

The West Indian manatee has two subspecies,

the Florida and Antillean manatee.

Manatees pronounced “MAN uh

TEES”, have been called many names,

including sirenians, sea cows and even

mermaids. The first Europeans to encounter

manatees thought that they were

seeing the mythically beautiful mermaids,

which were believed to be half

woman, half fish creatures. On closer

inspection however, they were disappointed

to see that these animals were

not quite as beautiful as they thought.

Manatees and dugongs are members

of the order Sirenia. Sirenians include

four living species: the West Indian

manatee, the West African manatee, the

Amazonian manatee, and the dugong.

The West Indian manatee has two subspecies,

the Florida and Antillean manatee. America. The Amazonian manatee

(Trichechus inunguis) is only found in

fresh water. It dwells in the Amazon

and Orinoco river systems of South

America. The West African manatee

(Trichechus senegalensis) lives in the

rivers and coastal waters of western

Africa. It is thought that Sirenians

evolved from four-footed land mammals

about 45-50 million years ago.

America. The Amazonian manatee

(Trichechus inunguis) is only found in

fresh water. It dwells in the Amazon

and Orinoco river systems of South

America. The West African manatee

(Trichechus senegalensis) lives in the

rivers and coastal waters of western

Africa. It is thought that Sirenians

evolved from four-footed land mammals

about 45-50 million years ago.