Vendors sceptical about lionfish

University of Southampton postgraduate researcher Fadilah Ali showing how to prepare lionfish to be turned into delicious lionfish and bake.

|

Lionfish and bake may taste delicious but the misconception that it is poisonous remains the biggest obstacle for its acceptance as an alternative to shark and bake.�This is the view of University of Southampton postgraduate researcher Fadilah Ali. Ali, the PhD candidate who has dissected more than 10,000 lionfish, told the Sunday Guardian via e-mail that the lionfish was not poisonous, but that the tips of its barbs contained venom instead. If it stuck someone, it would be painful but was not fatal, and no one has died from it.�

Ali said throughout the Caribbean there was a great misconception that the lionfish was poisonous and as a result there was a general unwillingness to eat the fish.�She said education via the media was the only way to clear up these misconceptions and also prove to people the benefits of eating lionfish.�

Ali said another means was to expose people to successful case studies using other islands like Jamaica and Belize which exported lionfish. She also gave examples of lionfish culinary competitions, a lionfish cookbook-proof that people were eating lionfish and surviving.�She said organising lionfish tasting events was another way to overcome this perception.�

Shark has been good�to the Fergusons

The Sunday Guardian returned to Maracas on Wednesday and asked vendors, fishermen and visitors for their comments after the first lionfish and bake taste-test was conducted at Richard's Bake and Shark shop, by Papa Bois Conservation director Marc de Verteuil, Institute of Marine Affairs coral reef ecologist Jahson Alemu and Ali on February 15.�The shark has been good to the Fergusons. Four out of the six shark and seafood shops at Maracas are owned by family members, creating a veritable shark-and-bake dynasty.�

Giselle Ferguson, from Richard's, said since the article was published in the Sunday Guardian's February 16 edition, four out of ten people came to the popular establishment asking if they had lionfish on the menu.�She said the other six stuck to the bake and shark staple that Richard's is famous for among tourists and locals alike. Ferguson said customers may probably want to try the lionfish, but they needed more knowledge of the species as they were afraid of the lionfish's venom.�

Gary Ferguson, the owner of Richard's and Giselle's brother, said, "A lot of people came and asked about the lionfish, but not everybody wants to try it.

'People asking for the fish'

"The feedback we got from the people was anything that is poisonous they don't want any part of it.�"They keep asking if I have and I tell them I don't. It was the environmentalists who brought just a few lionfish, and we prepared it in our kitchen for them to test."�Ferguson said people will know the difference between the shark and lionfish as they were two different textures and quality of meat.�He said perhaps lionfish could be on the menu in the future, as well as red fish or grouper and bake, but shark remained the main delicacy in T&T.

People came from all over the world to try Richard's shark and bake as it was also very healthy, hence the reason why most of the population loved shark, Ferguson said with a hearty laugh.�He said his grandmother, 95-year-old "Ma" Ferguson, the matriarch of the family, was living testament to the health benefits of eating shark and not eating meat, as she was very strong.�According to Ferguson, sharks don't develop cancer and were good to treat ailments such as arthritis and inflammation.

However, the manager of the US-based conservation group, Pew Charitable Trusts, Angelo Villagomez said sharks do not have cancer-fighting properties.

'I will lose customers�if I start to sell it'

Ferguson said sharks were very healthy to eat. His grandmother utilised most parts of the shark, using the liver to make shark oil, head, fins and bones which they all grew up on also.�Patsy Ferguson, of Patsy's Bake and Shark and Gary's aunt, said the lionfish was too dangerous to eat and was too much of a risk.�She said since the Sunday Guardian's lionfish story was printed, a lot of customers came asking if she was selling it as they wanted no part of it, believing the lionfish to be poisonous.�

Patsy said if she started to sell lionfish, she will lose customers. �She said, "When my customers come here they ask for shark or king fish, they don't want no other fish.�"People use to say we're selling catfish, that is a no-no, we sell strictly mako shark, blue shark or blacktip shark that comes from Suriname, we don't get any from Las Cuevas or Maracas.�"People used to sell catfish but not me or my family."�

Ian Ferguson, from Nathalie's Bake and Shark and Gary's brother, said people in Maracas were not accustomed or familiar with lionfish and their specialty was shark.�A bake-and-shark lover said she didn't ask what type of shark she was eating, but she enjoyed it and didn't think of any of the consequences. She said she wouldn't want to eat such a predator like the lionfish. �

Leo Kowlessar, a Trinidadian living in New York, said he didn't believe that sharks will ever get wiped out because there were so many different types of sharks all over the world, and if one species became scarce, they will find another shark species. �

Aboud:�Longline vessels decimating shark, other marine life

Speaking in a brief telephone interview from China, on Thursday, Fishermen and Friends of the Sea (FFOS) secretary Gary Aboud said the scores of Taiwanese longline fishing vessels operating in local waters were responsible not only for decimating shark species but were also depleting other marine life.�Sonny, from Canada, said lionfish can probably replace shark if it was being overfished.

Maria, from Venezuela said shark was not as popular in her homeland as here, however, it should not be overfished to the point of extinction. Terry Lee suggested creating�new and innovative dishes instead such as lionfish accra and pholourie instead of looking for a substitute for shark and bake.�Aria said she would have to taste it to make a judgment call.�John said he wouldn't eat lionfish because the venom it carried was enough of a deterrent.

Fisherman "Master Brother John" from the Maracas Fishing Depot said one of the fishermen received a puncture in his arm from a lionfish's barb in his net but the injury was not serious when he want for medical attention.�John confirmed the lionfish was in T&T waters, but they were only catching a few in their nets.�Fisherman Clement Vargas said if the lionfish was in abundance, it could be used as an alternative to shark, but so can other readily available species of fish.

Another fisherman named "Django" said those who fish had some species that they kept for themselves, such as "power," and they knew how to cook catfish and even stingray to make them taste like shark and the average consumer wouldn't be able to tell the difference.

Papa Bois launches�campaign to save the shark

Papa Bois Conservation launched its campaign to raise awareness in T&T about the worldwide threats to sharks from overfishing at the current unsustainable rate on February 23.�The launch took place at the Maracas turn-off, leading to the bake-and-shark haven in Maracas Bay.�The report was carried in the international media, such as the London Metro, Washington Post and Associated Press.�

De Verteuil said he was preparing to meet with the shark-and-bake vendors to do a presentation on shark conservation, the consequences of depleting shark populations, and the lionfish as a possible alternative to shark and bake.

Source

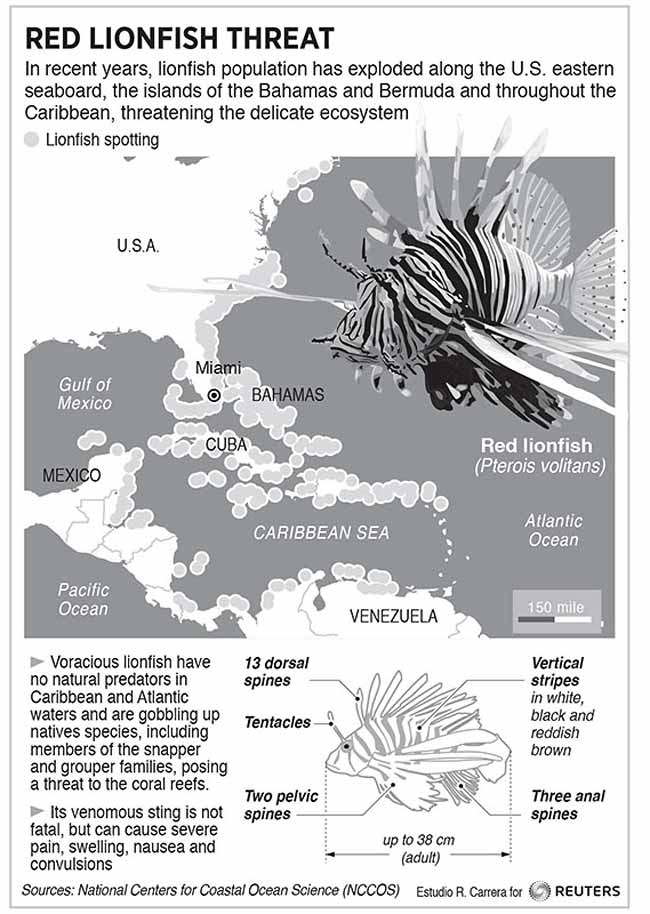

Invasive lionfish imperiling ecosystem

The South Pacific native with no known predator is eating its way through the Gulf and Caribbean.

It sounds like something from a horror film: A beautiful, feathery-looking species of fish with venomous spines and a voracious appetite sweeps into the Gulf of Mexico, gobbling up everything in its path.

Unfortunately for the native fish and invertebrates it's eating, this invasion isn't unfolding on the big screen.

In recent months, news has been spreading of lionfish, a maroon-and-white striped native of the South Pacific that first showed up off the coast of southern Florida in 1985. Most likely, someone dumped a few out of a home fish tank. With a reproduction rate that would put rabbits to shame and no predators to slow its march, the fish swept up the Eastern seaboard and down to the Bahamas and beyond, where it is now more common than in its home waters.

"The invasive lionfish have been nearly a perfect predator," says Martha Klitzkie, director of operations at the nonprofit Reef Environmental Education Foundation, or REEF, headquartered in Key Largo, Fla. "Because they are such an effective predator, they're moving into new areas and, when they get settled, the population increases pretty quickly."

The lionfish population exploded in the Florida Keys and the Bahamas between 2004 and 2010. As lionfish populations boomed, the number of native prey fish dropped. According to a 2012 study by Oregon State University, native prey fish populations along nine reefs in the Bahamas fell an average of 65 percent in just two years.

Lionfish first appeared in the western Gulf of Mexico in 2010; scientists spotted them in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, a protected area about 100 miles off the Texas coast, in 2011. Now scuba divers spot them on coral heads nearly every time they explore a reef. So far, significant declines in native fish populations haven't occurred here, but the future is uncertain.

'IMPOSSIBLE BATTLE'

"It's kind of this impossible battle," says Michelle Johnston, a research specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Galveston, who manages a coral reef monitoring project at the Flower Garden Banks. "When you think how many are out there, I don't think eradication is possible now."

Two nearly identical species are found in the Gulf. They grow to about 18 inches and have numerous venomous spines. Their stripes are unique, like those of a zebra. They hover in the water, hanging near coral heads or underwater structures where reef fish flourish. Ambush predators, they wait for prey fish to draw near, then gulp them down in a flash.

The fish mature in a year and can spawn every four days, pumping out 2 million eggs a year. They live about 15 years.

In the South Pacific, predators and parasites keep lionfish in check. But here, nothing recognizes them as food - those feathery spines serve as do-not-touch warnings to other fish. The few groupers that have been spotted taste-testing lionfish have spit them back out, Johnston says.

In the basement of the NOAA Fisheries Science Center on the grounds of the old Fort Crockett in Galveston, Johnston sorts through a rack of glass vials. Each one contains the contents found in the stomach of a lionfish collected in the Flower Garden Banks.

She points to a fish called a bluehead wrasse in one jar. "This little guy should still be on the reef eating algae, not here in a tube," she says. Other jars contain brown chromis, red night shrimp, cocoa damselfish and mantis shrimp, all native species found in lionfish bellies. "The amount of fish we find in their guts - it's really alarming. They're eating juvenile fish that should be growing up. They're also eating fish that the native species are supposed to be eating."

Lionfish can eat anything that fits into their mouth, even fish half their own size. They eat commercially important species, such as snapper and grouper, and the fish that those species eat, too. They're eating so much, in fact, that scientists say some are suffering from a typically human problem - obesity. "We're finding them with copious amount of fat - white, blubbery fat," Johnston says.

They can adapt to almost any habitat, living anywhere from a mangrove in 1 foot of water to a reef 1,000 feet deep. They like crevices and holes but can find that on anything from a coral head to a drilling platform to a sunken ship. They can handle a wide range of salinity levels, too. Their range seems limited only by temperature - so far they don't seem to overwinter farther north than Cape Hatteras, North Carolina - and their southern expansion extends to the northern tip of South America, although they are expected to reach the middle of Argentina in another year or two.

'A SNOWBALL EFFECT'

"As long as they have something to eat, they'll be there," Johnston says.

The impact of their invasion could become widespread, scientists warn.

In the Gulf, lionfish are eating herbivores like damselfish and wrasse - "the lawnmowers of the reef," Johnston calls them - that keep the reef clean.

"When you take the reef fish away, there's not a lot of other things left to eat algae," she says.

That creates a phase shift from a coral-dominated habitat to an algae-dominated one. "When you take fish away, coral gets smothered, the reef dies, and we lose larger fish. It's a snowball effect of negativity."

The only known way to keep lionfish populations in check, scientists say, is human removal.

That's why lionfish "derbies," or fishing tournaments of sorts, are popping up around the Caribbean and Gulf.

Locals are encouraged to kill and gather the fish, and in some places, including Belize, cook them up afterward.

The key is getting people to understand that lionfish are safe to eat - and tasty.

SOURCE