Click the image above to see a chart of Maya chronology

|

Click here for photographs of Maya Sites in Belize |

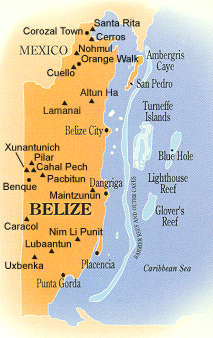

Several archaeological sites, described below, are open to the public. Four are visited widely by the public, and are soon to be made official archaeological reserves with the supporting facilities. Many other sites are located on private land and can only be visited if prior permission is obtained. Additional information about the ruins can be had by visiting or corresponding with the Department of Archaeology in Belmopan or with the Association for Belizean Archaeology(ABA) at the Center for Environmental Studies on Eve Street in Belize City.

It is generally thought that the population of what is now Belize was considerably greater during the Classic Maya Period than it is today; the plethora of Maya sites in the country today is testimony to this.

Click here for maps for nine Maya sites in Belize.

Click the image above to see a chart of Maya chronology |

Belize clearly lay in the Maya heartland: not only are some of the earliest sites, like that of Cuello in Orange Walk, found in the country, but the recent discovery of glyphs at Caracol, Cayo District, apparently portraying a military victory over Tikal suggests that some of the Belizean centres were supreme in the region.

This webspace describes the major, excavated sites in Belize.

Some, like those of Altun Ha and Xunantunich, are

located close to major roads. Others, like Lamanai and

Caracol, are more difficult of access. Yet it is this

difficulty which makes an excursion to Lamanai

unforgettable, for its remoteness and its partially

uncovered state heighten its splendour and mystique.

Lamanai again is just one of many examples of the beauty

not only of the temple-pyramids themselves but of their

surroundings: while the Maya warlords and priests

surveyed, from the pyramids' summits, their domain

stretching around them, we see below us the length of

New River Lagoon, silver blue and pristine. Likewise,

climbing the main temple itself is only part of the trip to

Xunantunich- the village of San Jose Succotz lies next to

the Mopan River, at the foot of Xunantunich; its people

are of predominantly Yucatecan Maya origin and the

village is famous for its fiesta and traditional dances; it

was also the base camp for one of the greatest Maya

archaeologists, Eric Thompson. The green river, rushing

over shallow rapids is a superb place to bathe (and to

wash clothes) after you've trekked or driven the mile or

so uphill to the temples and plazas themselves, from

whose summits Succotz and Benque Viejo lie below you,

the hills of Peten forming the western horizon.

Xunantunich- the village of San Jose Succotz lies next to

the Mopan River, at the foot of Xunantunich; its people

are of predominantly Yucatecan Maya origin and the

village is famous for its fiesta and traditional dances; it

was also the base camp for one of the greatest Maya

archaeologists, Eric Thompson. The green river, rushing

over shallow rapids is a superb place to bathe (and to

wash clothes) after you've trekked or driven the mile or

so uphill to the temples and plazas themselves, from

whose summits Succotz and Benque Viejo lie below you,

the hills of Peten forming the western horizon.

Before we look at the major sites themselves, it's to be remembered that other supremely spectacular sites were utilized by the Maya but now show no trace of that history: the Rio Frio cavern, from which Mayan remains have been excavated, is now purely nature's domain -the river has formed an immense tunnel through the limestone, opening the mountain spur at both ends; stalactites are still in dripping formation and petrified limestone waves form the floor. Close by, the Rio On cascades through some of the oldest rocks in Central America, forming natural pools. These superb sites are just an hour's drive from San Ignacio up into the Pine Ridge.

You need light-weight, comfortable clothing and shoes with a good grip. Long trousers are more suitable than shorts as they give more protection from insects and weather.

The rainy season lasts from June to November, but it can

rain at any time of the year. The rains are interspersed

with long periods of hot, dry weather. You need,

therefore, to have a hat and sunscreen available year

round and a light-weight raincoat is often useful. Insect

repellant is a must and a container of drinking water is

advisable, as several sites are remote from any facilities.

Santa Rita The modern town of Corozal is built over the ancient Maya center of Santa Rita. This site was important during

the Late Post Classic Period (c.a. A.D. 1350-1530), and was occupied up to the time of Spanish contact in the

1500's. The largest building in the central core has been excavated and consolidaced. Archaeological

investigations there have shown Santa. Rita to be the ancient province of Chetumal where a large part of the Post

Classic civilization once thrived.

Corozal is easily accessible by public transportation, and hotel accomodations are available in town.

The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel

by Ralph L. Roys [1930]

The Book of the People: Popol Vuh

Maya Hieroglyphic Writing (excerpts)

The Popul Vuh

excerpt from

The Mythic and Heroic Sagas of the Kichés of Central America,

by Lewis Spence; London [1908] 79,023 bytes

ancient Chetumal

Historical context

Mayan texts:

Yucatan Before and After the Conquest

by Diego de Landa, tr. William Gates [1937]

The best primary source on the Maya, ironically by the monk who burned most of their books.

by Delia Goetz and Sylvanus Griswold Morley

from Adrián Recino's translation

from Quiché into Spanish

[1954, copyright not registered or renewed]

by J. Eric S. Thompson [1950]

The site's strategic location attracted the

Conquistadores, who attempted to take the city and

establish a base there. Anthropologist Grant Jones has

traced the events that followed: "In 1531 Alonso Davila

set off by land to the province of Chetumal and travelled

southward through the Cochua and Uaymil provinces

with 50 men and 13 horses, hoping to discover gold

along the way. Part of his party eventually reached

Chetumal by canoe, carrying horses in double canoes

lashed together, finding it completely abandoned. The

Spaniards eventually attacked those who had abandoned

Chetumal for the site of Chequitaquil, several leagues up

the coast. Here they found their first gold, evidence of

the importance of long-distance trade for the Chetumal

economy. After this event armed rebellion broke out

throughout the region." Nachancan was the Maya

warlord who, during that rebellion, re-took Chetumal from

Davila.

Although they were driven out of Chetumal/Santa Rita, the Spaniards established an outpost at Bacalar and were successful in their attempts to conquer Northern

The site

The formation of Santa Rita dates from c. 2000 B.C. -from the beginning of Maya history; this is evinced by burial at the site which yielded pottery of the Swasey style, some of the earliest found in the Maya area. From c. 300 B.C. to c. 300 A.D. the settlement expanded but continued to be based primarily on agriculture.

The Classic Period at Santa Rita is marked by the site's only extant structure, a complex series of interconnected doorways and rooms with a central room containing a niche in front of which offerings were burned. Two important burials were unearthed there, the earliest dating to the Early Classic, containing an elderly woman with elaborate jewelry and polychrome pottery. A second burial dated to c. 500 A.D. was discovered inside an unusually large tomb and is probably that of a warlord who was interred with the symbols of his rule -a ceremonial flint bar and stingray spine used in blood-letting rituals. Many of the artifacts found in this tomb show similarities to those from Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala and Teotihuacan in Central Mexico, attesting to the international character of the site; Classic Period artifacts even include pottery of Andean origin.

The amateur and explosive archaeologist Thomas Gann discovered fabulous Mixtec influenced frescoes at Santa Rita at the turn of the century; these do not survive, but fortunately Gann's meticulous copies do. The most systematic series of excavations at the site was the Corozal Postclassic Project led by A. and D. Chase from 1979 to 1985.

The town of Corozal, founded in the mid 1800's, has slowly encroached on Santa Rita destroying large parts of the site, many of which disappeared into the streets of Corozal. In ancient times Santa Rita extended from present-day Paraiso in the north to the south end of Corozal and San Andres. The site, bordered on the east by the sea, is situated on the limestone plateau of which Northern Belize is composed and which supports a low forest in which game abounds. Just north of the site is the Rio Hondo, along whose banks are large areas of swampland in which the Maya created raised fields. These supported the cacao plantations for which the province was famous. The sea coast gave the site access to a wide variety of marine resources.

Santa Rita is located on the outskirts of Corozal Town just off the main road leading to Santa Elena and the Mexican border. Frequent buses between Belize City and Corozal pass by the site. There are two flights a day from Belize City. Accommodation is available in Corozal Town.

Chronology of the Ancient MayaThe following is the classification used in this text:

|

Located on a peninsula across from the town of Corozal and in the Bay of Chetumal, this site was important as a coastal trading center during the Late Preclassic Period (C.a 350 B.C. to A.D. 250). Its tallest temple rises 21 meters above the plaza floor and residences of the past elite are now being washed by the, bay waters. The name is Spanish for "hill" and the translation is "Maya Hill".

Cerros can be reached by a short boat ride from Corozal. Boats can be hired in town where hotel accomodations are also available. During the dry season, between January and April, one can reach Cerros by road in a rented vehicle passing such picturesque towns as Chunox, Progresso and Copper Bank and their beautiful lagoons.

Historical context

Cerros is a Late Preclassic centre with virtually no later

additions to its structures, indicating an early demise.

David Freidel's 1973-1979 excavations revealed that the

site underwent a transition "from local resource

dependency during its initial occupation to regional

interaction of goods and services during its final

occupation." It was, then, a trading centre probably

based on the sea-borne import of jade and obsidian. Its

early decline was possible due to the "general shift of

trade routes connecting the highlands and lowlands in

the Early Classic. "

Cerros is a Late Preclassic centre with virtually no later

additions to its structures, indicating an early demise.

David Freidel's 1973-1979 excavations revealed that the

site underwent a transition "from local resource

dependency during its initial occupation to regional

interaction of goods and services during its final

occupation." It was, then, a trading centre probably

based on the sea-borne import of jade and obsidian. Its

early decline was possible due to the "general shift of

trade routes connecting the highlands and lowlands in

the Early Classic. "

The site

The Cerro Maya ("Maya Hill") Archaeological Reserve consists of 52.62 acres and includes three large acropolises dominating several plazas flanked by pyramidal structures. Two structures are known to possess facades with 2 - 4 metre (6.5 - 13 ft.) high masks. Tombs and ball courts have been excavated and many artifacts found, demonstrating the importance of the site during the 400 B.C. - 100 A.D. period. The civic- ceremonial centre covers an area of .75 km. (.5 sq. mile) with the tallest structure rising 22 metres (72 ft.) above plaza level. The site's adjacency to the sea has meant that the two large structures are being eroded; the rate of erosion and lack of funding for maintenance has unfortunately necessitated covering the masks with plaster.

Thomas Gann was among the first to recognize the existence of a Maya site at Cerros, but it was not until 1969 that Peter Schmidt and Joseph Palacio visited it and registered the site with the Department of Archaeology.

The land on which the site is located was acquired by Metroplex Properties Inc., a Texas operation and a development foundation called the Cerro Maya Foundation was formed in Dallas as a nonprofit organization to excavate, consolidate and reconstruct the ceremonial centre as a tourist attraction: plans were made for a research centre, on-site museum, hotel and swimming pool. The Cerro Maya Foundation under Metroplex Properties Inc. subsequently went bankrupt and the large-scale development of the site was never realized.

The site was eventually surveyed, excavated and

partially consolidated from 1973 to 1979 by David Freidel

of Southern Methodist University; Freidel focused on

the ceremonial centre, its outliers and on the importance

of trade at Cerro Maya. In 1983 Cathy Crane, a doctoral

student at the same university tested ancient canals and

associated structures at the site for pollen and other

organic remains. Since then no further work has been

carried out. Cerros was a thriving community in the Late Formative Period due to its location on the circumpeninsula trading route. A fishing village for its first 300 years, Cerros covered about seven acres and consisted of approximately 38 pole and thatch buildings which would have housed approximately 500 people. Occasionally built on low clay platforms, these huts were rethatched every 30 years much as they are today. Burial and storage pits were sunk into the trash accumulations (midden) in the adjacent patio areas. The importance of trade at this early period is indicated by a large low platform and jetty on the water, west of the village. Cerros was the main distributor of salt from the north coast mining communities and is known to have traded chert tools from nearby Colha, up the New River, to Lamanai. There is evidence of non-local materials such as volcanic hematite and greenstone. Obsidian and jade materials came from as far away as Guatemala and El Salvador. The cerros ceramics combine foreign artistic elements and firing techniques with local ones.

The fluorescence of the lowland Maya centers and their demand for trade goods triggered a new phase of development at Cerros which transformed the village to an urban center. A 3600 foot canal, 18 feet wide and 6 feet deep, was built to surround 91 acres and served as part of the drainage system for the maize, squash, bean and cotton crops. Within this structure was built a ceremonial center which included four pyramids, their associated plazas and buildings, 103 public and private structures, two ball courts and accommodations for approximately 400 people. House mounds decrease ,in density outside the canal perimeter. All of the pyramids were decorated with stucco images but have been temporarily covered by the Belizean government to prevent the limestone from weathering.

The Mesoamerican ball game was both recreational and ceremonial in nature. Often the game was played to determine the outcome of future events (the losers being sacrificed) but it was also played for recreational pleasure. The ball game was played with a solid rubber ball in a formal court. The object was to score by propelling the ball through rings on the side walls. Some courts, lacking rings, have markers on the sides or center of the court floor.

The two ball courts at Cerros are an interesting feature. A common occurrence at preColombian Mesoamerican sites and often found at Late Classic Maya sites, it is rare that they appear during the Early Classic Period. It is assumed the game originated in the lowlands (the ball was made of rubber, a lowland plant) but only two ball courts from the Early Classic Period have been reported, at Palenque and Copan. It is interesting that both cities are located on the periphery of the Maya area, as is Cerros.

Dr. Freidel suggests that a change in the way the game was played would affect the court construction and perhaps evidence from this period remains unrecognized. Perhaps the reasons the game was played did not exist throughout the Early Classic.

The open-ended ball courts consist of a raised playing alley flanked by two parallel buildings. These buildings have broad, low benches that face the alley and have battered, sloped surfaces, indicating they were within fair play. The central court markers have been removed. There were summit access stairs at the backs of the buildings.

Construction technique generally followed that of the other major buildings at Cerros. An initial layer of white lime, followed by a layer of dark grey marl and trash (habitation debris), then by brownish/red dirt with cobbles which was then covered by a thick hard plaster floor over the playing area (the alley and walls).

At the close of the Formative Period trade routes changed. Overland routes controlled by the other Maya centers came into primary usage while the coastal routes became less frequented. Cerros declined and the main buildings were ritualistically abandoned. Pottery was smashed and deposited in front of the facades, fires were set against the masks and the stone markers in the ball courts were removed A dispersed population continued to live outside the ceremonial districts until the Early Classic Period, but Cerros never regained its position of importance.

Cerro Maya's location on the shore of Corozal Bay permits a range of water sports; part of the site remains under forest coverage, with the panorama of the Bay below.

New River empties into the Bay 2 kilometres (1.5 miles) southwest of Cerro Maya. The river, with its rain- forested banks and associated wildlife formed an important link with Lamanai when the site was flourishing.

Cerros is a short boat ride from Corozal Town, where boats can be hired and accommodation is available. During the dry season, January to April, Cerros can be reached in a rented vehicle by the road which passes through Chunox, Progresso and Copper Bank villages with their beautiful lagoons. No facilities are available at the site itself and insect repellent is needed.

"Submerged Crocodile "

"Submerged Crocodile "This is one of Belize's largest ceremonial centers. In addition to its display of the more exotic features of the ancient Maya in art and architecture, Lamanai (corruption of "Lama'an/ayin", Maya) also had one of the longest occupation spans dating from 1500 B.C. to the 19th century, which includes the contact period. Historical occupation is represented in the remains of two Christian Churches and a sugar mill. The name of the site was recorded in historical accounts and is Maya for "submerged crocodile".

At present Lamanai can only be reached by road from San Felipe Village in a strong vehicle during the dry season. However, the more popular route is by the New River Lagoon, a waterway rich in the natural history of the country Boats can be hired from Guinea Grass or Shipyard.

There is no public transportation from Orange Walk Town to Guinea Grass or Shipyard but taxies and rental vehicles are available both in Belize City and Orange Walk Town. Hotel accomodations are also available in these two locations, the nearest being Orange Walk Town, some 30-45 minutes away.

Click here for photos.

Click here for a rotating panorama of the view from the top of the largest temple at Lamanai.

Lamanai: A great place to visit

It's that time of year when nearly every airplane that leaves Belize City is packed full. And this year is no exception...but there is one difference. Where traditionally the passengers were mostly Belizeans headed for summer holidays in Miami, New York, L.A. or Chicago, the majority now seems to be foreign tourists returning from happy holidays in Belize. And what about the Belizeans? It seems that a growing number are beginning to discover what the tourists found out long ago: Belize is a great place for a vacation. We've been singing that song for almost a decade and over the next few months we'll be revisiting some of our favourite places that make great day or weekend getaways. Tonight we travel to the Orange Walk District and the magnificent Maya site of Lamanai. William Neal is our host and you can be the judge of whether his looks and talents have improved since this story first aired in 1993.

William Neal The trip up the river takes approximately one hour and the pristine environment adds to the mystique and adventure of Lamanai. The boat journey comes to an end as you enter into the New River Lagoon and the anticipation begins as the main temple can be seen towering above the forest.

Nazario Ku, Lamanai Curator Nazario Ku has been the curator at Lamanai for a year, but has worked at different sites around the country for over ten years.

Nazario Ku "Maya here started as a settlement around 1500 B.C. and they flourished as a city state around the 2nd century B.C., which is a long time between. This is one of the uniqueness of Lamanai because it was inhabited for around 3,000 and over. The highest peak of the Lamanai was about the 6th to the 7th century A.D. even though at the 10th century A.D., they were performing sacrificial rites. There were still offerings to the Gods and what makes Lamanai unique, is that when other city states were falling into decline, Lamanai was still going on strong." Lamanai is located on 950 acres of archeological reserve and features more than a hundred minor structures and over a dozen major ones. This ruin called the Temple of the Mask, houses a stucco mask of an Olmec God, which some believe to be of Kinich Ahau, the Sun God. The size of this temple seems impressive until you approach the one next door, which is one of the tallest buildings in the country, believed to be the temple of sacrifice at Lamanai.

William Neal Although not half as fantastic as it must have been in ancient times, when men, women, and children crowded the market place exchanging exotic goods from all over the Maya world.

William Neal In the game, warriors competed to win the honour of being sacrificed on the high altar, so that their blood could renew the life of the Sun God. Life at Lamanai was highly organised and the people were self sufficient, though shells, jade and clay found in the area indicate plenty of outside contact.

William Neal

Nazario Ku

William Neal In its own way, the ornate craftsmanship of the brick and ironwork is as much a wonder as the limestone and mortar ten centuries earlier. The English mill, the Spanish church and the Maya temples have created an attraction for tourists that is among Belize's best. A number of companies operate tours to Lamanai. Most boats leave from the vicinity of the Tower Hill Bridge. For lots of pictures, see:

|

Lamanai has a special place in Maya history because of

its early greatness -structure NIO-43 is the largest

Preclassic structure known in the Maya area- and

because of its longevity: the site was occupied

throughout the Postclassic until at least the mid-

seventeenth century.

Lamanai has a special place in Maya history because of

its early greatness -structure NIO-43 is the largest

Preclassic structure known in the Maya area- and

because of its longevity: the site was occupied

throughout the Postclassic until at least the mid-

seventeenth century.

Lamanai is an ancient Maya center known to have been occupied continuously for two millennia (approximately 300 B.C. - AD. 1680). Narrowly stretched along the west bank of the New River Lagoon, Lamanai illustrates an unusual settlement pattern among Maya sites. Usually built as one or more ceremonial plazas encircled by residential clusters, Lamanai ceremonial areas are close to the river with residential areas to the north, west, and south. To date, only 5% of the site has been investigated (by Dr. David M. Pendergast of the Royal Ontario Museum). As most of these buildings are ceremonial structures, research is weighted on the side of the ritual. How ever, these structures are the foundations of social edifice and therefore tell us much about Maya society.

Because of the late occupation, the site's name -

"Lamanay" or "Lamayna"- was recorded by Franciscan

missionaries in the seventeenth century and is thus the

original Maya name. In 1978 it was realized that

Lama'an/ayin means "Submerged Crocodile", a fact

which, as archaeologist David Pendergast points out,

helps to explain the numerous crocodile representations

at the site, including figurine headdresses, vessel

decorations and the headdress of a four metre-high

limestone mask on the platform of a 6th century temple.

The site centre occupies .75 sq. km. (.5 sq. mile) with

residential and minor structures distributed over an area

of 950 acres, the present-day extent of the official reserve.

Pollen evidence shows that maize was being cultivated at

the site c. 1500 B.C. but we know little of what happened

between then and c. 500 B.C., the time from which the

earliest pottery fragments found at the site derive.

The site centre occupies .75 sq. km. (.5 sq. mile) with

residential and minor structures distributed over an area

of 950 acres, the present-day extent of the official reserve.

Pollen evidence shows that maize was being cultivated at

the site c. 1500 B.C. but we know little of what happened

between then and c. 500 B.C., the time from which the

earliest pottery fragments found at the site derive.

From that time the story of the site has been revealed by archaeologists digging through the layers of the past to unearth early structures beneath later ones: buried deep within the 6th century masked temple mentioned before was a small, superbly preserved Late Preclassic temple dating from c. 100 B.C. with plaster masks resembling those from Cerros. The massive NIO-43 is of the same date but it too had been modified several times, the last being in the Late Classic, c. 600 A.D.

Late in the Classic Period the northern parts of the site

appear to have been de-sacralized: areas of formerly

ceremonial ground were converted for residential use,

while the southern sector became the focus of ceremonial

activity. In the southern sector, Classic structures were

surmounted by Postclassic ceremonial buildings and new

religious structures were erected. Plausibly the smaller,

less spectacular nature of the Postclassic structures

reflects a lessening supply of labour and a less

hierarchical society than that of the Classic.

In addition to its Maya structures Lamanai also has

historic archaeological remains including two 16th

century Christian churches, a 19th century sugar mill

intact with flywheel and boiler, and a sunken, bricklaid

reservoir. Occupation of Lamanai over the centuries thus

includes Maya of all periods, British sugar cane growers

and sugar manufacturers, Spanish clergy and Chinese

factory workers. European, North American and Maya

materials were used here so that Lamanai artifacts are of

stone, clay, wood, bone, shell, jade, gold, copper, glass,

iron and even liquid mercury.

Generally, site occupation during the Protoclassic Period was developed and extensive. Residential and ceremonial concentration was in the northern precinct and the lagoon shore. The Protoclassic is characterized by diversity in architectural form in contrast to the rigidity of control shown in ceramics and the general nature of dedicatory offerings.

The Classic Period ceremonial constructions are concentrated more toward the central area; however, there was continued construction in the northern precinct and new construction in the southern area. The residential area in the northern precinct continued to be in use.

It appears that many were leaving these northern centers toward the end of the Late Classic Period, but there was continued Classic Construction in the southern precinct. Motifs developed here before the 12th century were later adopted at Mayapan, a large Yucatan Maya center occupied from 1200 - 1750 A.D.

The Postclassic Period was generally a time of gradual decline, however, the population at Lamanai was ceremonially active and in communication with other areas of the Maya lowlands. This indicates that the complete breakdown of Classic societies, as is characteristic of neighboring centers, was not the case here. Lamanai stability may be a result of strong community leaders or due to the resources of its location; such as food supplier and trade.

In the early 16th century, Spanish missionaries arrived and built a church south of the southern precinct. The community also moved south either before or after the Spanish came. Modem squatters live in scattered settlements along the lagoon.

N9-56, the dominant structure of the central ceremonial precinct, stands 56 feet high. This is the most thoroughly investigated of the larger buildings at Lamanai and spans a longer period of time than most. The primary structure, built during the Early Classic Period, is exceptionally well-preserved with architectural features such as corner stairs and molding free terraces. Dating is based on a vessel in the interment at the base of the structure, at the front of the stairs. Although not unique to Lamanai construction or grave content, it represents a major deviation from typical Maya tombs which usually consisted of a vaulted chamber with or without a bench on which the body was lain. A grave of similar construction was found at Cuello and was dated 200-300 A.D., much earlier than the 400700 A.D. date indicated at Lamanai.

The tomb at Lamanai was constructed on the floor atop a pile of burned wooden artifacts. The body was positioned upon the pile so that the hips rested in a larger redware basalridge dish, while stones and earth supported the upper body in the unburned area. A wall of stone and clay underlaid the burned material and surrounded the body to a height of 11 inches. A red pigment was applied to the corpse and then layered with clay. The area was then filled with such artifacts as wooden-backed jade ear ornaments carved with human faces, wooden figurines with jade ear ornaments, and platted and corded textiles. A wooden framework was built atop the foundation and covered with lime plaster bandages made of a course textile, creating a cocoon effect. Fine red textiles overlay the courser material. Mortar and stone was then built around the cocoon with a row of capstones, covered in a mass of chert chips, obsidian flake blades and cores.

It was customary to raze structures before modification. The two-chambered building that once stood atop this structure was destroyed, leaving only the building layout in black paint on the platform surface, a feature seen at Tikal but not previously encountered in the central lowlands.

When razed, certain parts of units were destroyed or left in place, often creating problems for engineers of the new structure. The remaining units, in this case, are large, unusual masks on the stairside outsets on the south side of the structure. Unfortunately, the upper mask was removed during construction, so only the back panel remains. The lower mask resembles Olmec (an influential Gulf Coast culture of the 1st millennium B.C.) iconography though the treatment of the mask is not in that style. Usually masks are made of stucco laid over a basic framework but this one is made of stone with a grey stucco coating of ash, charcoal and plaster. Lacking part of the frontal headdress which was removed to build the small stair, the mask originally had crocodilian features.

Masks partially excavated on the north side closely resemble those at Cerros. These features reinforce the theory that the correct name of the site is "Lama'an/ayin."

Crocodiles occupied an exalted place in the Maya pantheon and it is believed they were protected rather than offered in religious rites since no interment has included crocodilian remains.

Use of N9-56 during the Late Classic Period was inferred by Mayapan type figurine censers, broken and scattered over the front, sides and back of the mound in the customary ritual manner. This debris overflowed in front of this structure, onto a group of small low platforms (N9-56) built during the Late Classic Period. The platforms were faced with vertical stones and coated in stucco. The central platform was built to support a Classic Period stela (a dedicatory monolith), relocated here from an unknown location in the Late Classic Period. Its carved side once faced an uncarved, relocated stela to its south.

9-2 is an isolated major building on the lagoon north of the N9-56 group, and has expanded our information concerning Protoclassic use for the area. The platform contained two offerings resembling those from N9-56 platform and indicate a 1st century A.D. date. The P9-2 platform itself does not appear to have supported a chambered structure.

similar to P9-2, in that there was no chambered building atop its center. Unlike P9-2 there was a building on the extension which overlooked the harbor.

P9-25 is the largest complex at the northern end of the site. A platform 297 x 363 x 59 feet supported buildings 30 feet high. Final modification occurred around 400 A.D. but earlier constructions are indicated; a project for future excavations.

The harbor is now seen as a large depression. The rational behind calling this a harbor rests partly on its shape and that it holds water during the rainy season. (Excavation is now, under consideration.) In areas bordering the harbor, there is ceramic evidence of Late Protoclassic construction.

N10-43 is the tallest structure at Lamanai. Reaching 33 meters, its building sequence is the most securely dated Preclassic structure in the Maya area. Plastered surfaces and hearths indicate residential use of N10-43 before it was chosen as a ceremonial site.

A second century B.C. construction offering from within the building contained a redware dish with flaring sides. Inside the vessel was a juvenile bird skeleton with its beak and frontal skull missing as well as the bones from one or more other birds. The bulk of construction was completed in the Protoclassic Period. An early version of the Lamanai building type is characterized by a large multi-terraced platform, without a chambered building at its summit. Masks flank the lower center and side stairs where there is a large landing that supported a platform which served as a base for a chambered structure. Three sets of stairs (referred to as a tripartite pattern) were built both at the lower and upper levels to scale the side of the building. Atop the upper stairs were two small chambered buildings built upon double terraced platforms which face inward toward a third unit. This unit also has a tripartite pattern of steps flanked by masks, but there is no structure at its summit. This upper structure arrangement is unique at Lamanai though the tripartite stairs are typical Classic innovations. An offering of ceramic vessels within the building suggests a date of 100 B.C.

During the Late Classic Period, N10-43 was drastically reconstructed. A long, single room building which spans the first landing replaced the small structure mentioned above. The tripartite stairs on all three levels were made one and the summit structure was removed.

An offering consisted of obsidian cores, thousands of blades and chips, jade, shells, and a large black on red bowl probably related to those found in N10-9. N10-43 continued to be used during the Postclassic Period as was most other parts of the southern ceremonial area. An offering in the debris at the base of the structure contained a vessel and a single jade bead over which is a fair amount of Postclassic ceramics.

The ball court lies south of N10-43 and. was built during the Late Classic Period, a time when the northern district reflects diminishing use. It is in poor condition and its open ended playing area is rather small. Underneath the gigantic marker disc which covers most of the floor surface was an offering of a lidded vessel. Inside were miniature vessels and small shell and jade objects. These latter objects rested upon a pool of mercury, an element previously known only from the Maya highlands.

10-7 The initial construction for N10-7 is a low platform built during the Middle Classic Period. Overlying a burial cut into the platform, the major construction was a single effort at the end of the Classic Period. Intrusive burials into the upper core indicate continued use to Middle Postclassic times. The building was in ruins by the end of the 14th century A.D., indicated by the age of the midden mound covering its south side.

N10-2 is a small ceremonial building located on the west side of the southern plaza and was the focal point of Postclassic construction. Two Early Classic structures are modified by a sequence of four buildings. Since razing was customary, most of the information is in reference to the second modification. This Postclassic effort resembles northern Yucatan structures in that the front looked like a columned portico, but the building materials are different. The building sat upon a platform faced with small, rough stones. The single room had a plaster floor and thin, wattle and daub walls. Two rows of wooden columns supported a roof of timber, matting and other materials. A small square altar was set in the center, toward the back of the room.

Fifty burials were found in the building core, 17 unaccompanied by artifacts. Twenty-six were typical Postclassic internments with one or more ceramic vessels smashed and strewn over the graves. In most cases, only one piece of each vessel was missing, suggesting that retention of fragments was of ceremonial value. There were 26 burials associated with the second building effort including a double-pit inhumation. An adult male was seated in the pit with a pyrite mirror, a copper bell and gold sheet coverings from perishable objects such as wooden disks or staffs. The copper objects associated with N10-2 burial include simple bells and strapwork rings which are likely clothing or ornaments with cruciform or single strap attachments. Two-bell headed pins to which cloth fragments adhered were found in situ indicating use as a fastener of a warrior's garment at the hip. Three censers were found in the upper pit, one containing a pair of chile-grinding vessels. The surface north of N10-2 was littered with Tulum (a Postclassic site on the Yucatan coast) shards.

N10-9 is the primary structure of the southern precinct and was probably built in the Early Classic Period. This is an estimate based on Late Classic ceramics found at higher stratigraphic levels and an absence of them at lower levels. A cache of jade and obsidian found within included large quadrangle-shaped jade earrings of Classic style which lends this estimate credibility.

In general, the form of a construction offering varies not only in size and content, but also in its location within the structure. They are commonly found beneath the stairs, inside the chambered buildings. Protoclassic and Early Classic offerings typically contained two vessels with objects inside. Obsidian and jade caches are typical of the Late Classic Period.

Late Classic building modifications, characteristic throughout this site, show a definite pattern of replacing a tripartite stair with a broad single stair. The strict following of architectural cannon is in contrast with the diversity of building types found at Altun Ha dating to this same period. Modification of N10-9 included new stairs and stairside outsets leaving the terraces of the primary structure exposed. The building followed architectural cannon with a new chambered building across the center of the stairs and it had no building at its summit. Within the new building was found offerings of a large dish with an animal motif, a large black on red bowl, and a mosaic jade mask.

During the Postclassic Period, Lamanai continued to flourish while other centers such as Altun Ha showed sharp decline. This is evidenced from the periodic repair of the exposed platform and stairs mentioned above, which indicate that ritual continued throughout this period.

Abandonment of N10-9 is signaled by the large amount of pottery deposited on the front stairs at the close of the Postclassic Period. Midden mound was begun in the plaza on the east side of N10-9 and eventually covered its base, the south side of N10-7 and overflowed along the rear side of N10-2.

N10-1 is a small platform in the center of the southern plaza. The primary structure contained two burials. The interned ceramics found here filled in gaps of the ceramic sequence for the 12th century A.D. Ceramics from the earlier internment included domestic wares and a Chicken (X) Fine Orange vase. The later internment included a large lidded censer which contained an adult male skeleton placed on a pile of 18 broken censers, bowls and jars. It is inferred that this was a person bearing high status since burial in No10-1 or N10-4 would have been prestigious. This is due to their proximity to N10-2, a focal point of Postclassic ceremony.

The ceramic style here and in N10-2 resembles those of Mayapan (1250 A.D.); i.e., serpent motifs and segmented basal flanges, commonly with border lines and vertical-line ornamentation or center notches. However, the radiocarbon dates (from N10-2) indicate an earlier date of 1140 A.D., pointing not only to a fully developed ceramic complex in Lamanai in the Early Postclassic Period, which effected change in ceramic styles at the important Late Classic centers.

N10-4 borders the plaza to the east. The primary structure is Classic. Razing demolished the building atop it, which was soon replaced by a single unit of Postclassic modification containing forty-seven burials, interned at varying times, all placed in a single unit. One of these is dated to the 15th or 16th century, a period not well evidenced elsewhere at the site. Grave goods included Tulum Red tripod dishes, carved redware censers and uniquely styled bowls, a large pierced stucco columnar censer, a copper bell and two carved bone tubes; one pictures a person in ornate dress complete with a bird headdress.

In the early 16th century the Spanish missionaries arrived and built a church one half mile south of the Postclassic district. Two mounds adjacent to the church may indicate the community had also moved south. A Postclassic ceremonial building was modified with front and back stairs and used as a burial mound for Christian converts over a period of 70 years. Though the bodies are interned haphazardly, it is a chance to observe for the first time in the Maya lowlands a population of a definite period. The statistics gleaned from such a find can answer many questions about mortality curves, sex ratios and pathologies. The major grave items were bone rosaries. The church itself was abandoned in 1640-41, known from the reports of Fathers Orbita and Fuensalida. The Maya took up residence in the building for approximately 50 years as indicated by midden refuse and a burial. The ceramics are indistinguishable from those of the Postclassic indicating that 16th to 17th century occupation at the other sites may also be indistinguishable.

Thomas Gann, the British medical officer and notorious amateur archaeologist was the first, in 1917, to visit the site in modern times; he excavated a stuccocovered and painted stela at the site of the 16th century church. J. Eric Thompson passed by the site in the mid-1930's and William Bullard Jr. explored it and made surface collections in the early 1960's. Thomas Lee of the New World Archaeological Foundation made another small surface collection in 1967.

Aside from looters and a few visiting archaeologists, no one did any substantial work at the site until David Pendergast of the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, began a long-term programme of excavation in 1974. A four-year restoration and consolidation programme was expected to commence in 1988.

Lamanai lies on New River Lagoon, suitable for swimming and water sports. The 950-acre Archaeological Reserve is now the only jungle for miles around the flora is once again of the primary rain forest typ with massive trees, forest canopy and humid atmosphere. As a result, wildlife is already on the increase in 1986 it was estimated that at least three families of howler monkeys were residing in the central portio of the reserve alone. Many species of water birds live along the lagoon and are easily viewed by those travelling from Shipyard to the site -a route of delight in itself. A second route, not accessible during the rainy season, is by road from Orange Walk Town via San Felipe.

Lamanai lies at the centre of the tourist zone in Orange Walk District and its links with the Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary 8 miles east of the reserve, place it at the heart of Belize's natural history.

Lamanai has restrooms and a picnic area. There is no public transport from Orange Walk to Shipyard or Guinea Grass but taxis and rental vehicles are available in Belize City and Orange Walk Town. Hotel accommodation is also available in those locations, the nearest being Orange Walk Town, some 30-40 minutes away.

For an incredible on-line resource on Lamanai, CLICK HERE.

Related Links:

Nohmul is located in the sugar cane fields behind the village of San Pablo. The site entrance is one mile down the road going west from the center of the village. Public transportation from Belize City, Orange Walk and Corozal passes through the village of San Pablo several times daily. Accomodations can be found in Orange Walk Town 8 miles away.

Historical context

Nohmul's early extensive occupation -during the Late Formative- was associated with drained fields (in the Pulltrouser Swamp area, this association being amongst the first to be demonstrated in the Maya lowlands). The site declined, becoming a "ghost town" in the Early Classic, the acropolis being abandoned as a public place. Then, in the Terminal Classic/Early Postclassic the acropolis was re-used as the locus of residences; at that late date Nohmul was apparently governed by a non- local elite, probably of Yucatecan origin.

The focal ceremonial structure is a 50 by 52 metre

rectangle 8 metres high. This massive acropolis is of Late

Preclassic date; traces of a huge, multi-sided ' post-built

Classic structure have been found on its southern end.

The acropolis dominates the main plaza and surrounding landscape. Excavations in 1986 showed that the structure had been rebuilt three times: Thomas Gann had removed the uppermost temple in his search for burial vaults below. The partially excavated stairway on the pyramid's southern terrace belongs to an earlier construction and the walls within the looters' tunnel on the east side belong to a yet earlier phase.

Archaeological work

In 1972 Ernestene Green of Western Michigan

Univversity did test-pitting in the Nohmul area as part of

her location analysis of sites in Northern Belize. Mapping

and small-scale excavation was done under the direction

of Norman Hammond in 1973, 1974 and 1978.

In 1982 Hammond began the full Nohmul Project and by

1986 the ceremonial precinct and outlying areas

including raised fields had been excavated. Structural

consolidation has begun, with both preservation and

tourism in mind.

The focal structure at Nohmul, which lies amongst sugar

cane fields, is the highest landmark in the Orange

Walk/Corozal area; it is located a mile from the Northern

Highway and is part of the twin villages of San Pablo and

San Jose. Seven miles from Orange Walk, Nohmul is easy

of access and has educational as well as tourist

potential.

The site entrance is one mile along the road from San

Pablo; Sr. Estevan Itzab must be contacted before

visiting the site or upon return -his house is across from

the water tower. Buses from Belize City, Orange Walk

Town and Corozal pass through San Pablo several times

daily. Accommodation is available in Orange Walk

Town; at the site itself there are no facilities.

Cuello: Cuello is a small ceremonial center, but archaeologically important for the earliest Maya occupation dates which

were recovered there. Occupation at Cuello was as early as 2500 B.C. and as late as A.D. 500. A Proto Classic

temple has been excavated and consolidated and lying directly in front is a large excavation trench, partially

backfilled, where the archaeologists were able to gather this historical information that revolutionized previous

concepts of the antiquity of the ancient Maya. The site took the name of the people who own the land of its

location.

The site occupies the compound of the local rum distillery of the same name. It is about 4 miles from Orange

Walk Town on the Yo Creek Road. Taxies are available from Orange Walk Town.

PLEASE NOTE that permission must be obtained from the Cuello family at the distillery prior to or on

entering their cattle pastures through which one must pass to reach the site.

Historical context

Cuello is part of the beginning: with occupation dating

from 2500 B.C., it is one of the earliest known Maya

sites.

Cuello, named after the people on whose land it lies, is a

minor ceremonial centre. While scientific research has

delved deep into Cuello's past through its stratified

underground layers, above ground what is seen is the

remains of the later ceremonial centre and settlement

area.

The ceremonial precinct consists of two adjacent plazas.

There is a main pyramid or temple in each plaza with

small palace and civic structures flanking them. Two

chultuns -undergound storage chambers- occupy the

platform of the ceremonial precinct.

While Classic Period structures have been identified at

the site and test excavated, the emphasis has been n the

centre's early phases.

The importance of the site -a regional centre of government according to Norman Hammond- is evinced by the 20 sq. km. (7.5 sq. mile) settlement area around the centre, encompassing lesser foci such as those in San Luis and San Estevan. The late, Yucatecan influence noted above has also been found elsewhere in Northern Belize, for example at Santa Rita.

Nohmul, situated on the low limestone ridge east of the Rio Hondo on the Orange Walk - Corozal boundary, was first recorded in 1897 by Thomas Gann, who described the great pyramid as a "signal or lookout mound". Gann returned to the site in 1908 and 1909 to dig burial mounds which yielded polychrome vessels and human effigy figures; in 1911 and 1912 he did surface collection of effigy incensario fragments in one of the site's outlying mounds, and in 1935 and 1936 he and his wife excavated in the main group and settlement areas. The Ganns uncovered tombs and caches which yielded human long bones, jade jewelry, shells, polychrome -vessels, chultuns and artifacts of flint and obsidian, most of which were taken to the British Museum.

During the construction, in 1940, of a road from San

Pablo to Douglas one structure was partially demolished for road fill and at least three burial chambers were uncovered, one of which was smashed and looted by the time A. H. Anderson and H. J. Cook got to the scene. Twenty-four vessels were salvaged from this wreck; many of them are our prime national exhibition material today. Tragically, these artifacts are only a fraction of the contents of those three rich tombs.

Locale and access

the Maya genesis

On the high ground between the Rio Hondo and New River, west of Orange Walk Town, lie the remains of one of the oldest settled societies in Mesoamerica. Cuello takes its name from the current landowners, the Cuello family. Cuello, with its clear stratigraphic sequences, reveals important information on the Formative Period Excavations by Dr. Norman Hammond of Rutgers University show an early transformation from a farming community to a ceremonial center. Developments in building, crafts, trade, maize agriculture (milpa), and human sacrifice indicate that the features of the Classic Maya civilization may have had their inception here in the lowlands rather than in Mexico or the highlands as previously believed. There are two adjacent plazas containing pyramids and platforms which date to the Classic Period. Earlier occupation is concentrated to the southwest underlying 26 centuries of expansion. The oldest platform is the earliest known example of plastering in the Maya area. At the lowest levels was found Swasey ceramics, a sophisticated complex, consisting of 25 varieties; the most abundant is known as Consejo red Swasey is the oldest pottery known in the Maya lowlands and one of the oldest ceramic traditions in Central America. This important discovery expands the known time span of the Maya culture to 2400 B.C.

On the high ground between the Rio Hondo and New River, west of Orange Walk Town, lie the remains of one of the oldest settled societies in Mesoamerica. Cuello takes its name from the current landowners, the Cuello family. Cuello, with its clear stratigraphic sequences, reveals important information on the Formative Period Excavations by Dr. Norman Hammond of Rutgers University show an early transformation from a farming community to a ceremonial center. Developments in building, crafts, trade, maize agriculture (milpa), and human sacrifice indicate that the features of the Classic Maya civilization may have had their inception here in the lowlands rather than in Mexico or the highlands as previously believed. There are two adjacent plazas containing pyramids and platforms which date to the Classic Period. Earlier occupation is concentrated to the southwest underlying 26 centuries of expansion. The oldest platform is the earliest known example of plastering in the Maya area. At the lowest levels was found Swasey ceramics, a sophisticated complex, consisting of 25 varieties; the most abundant is known as Consejo red Swasey is the oldest pottery known in the Maya lowlands and one of the oldest ceramic traditions in Central America. This important discovery expands the known time span of the Maya culture to 2400 B.C.

The site

Archaeological work

In 1974 representatives of the Cuello Brothers Distillery, on whose land the site is located, reported the bulldozing of mounds there and the site was formally registered by Joseph Palacio, the Archaeological Commissioner.

In 1975 Duncan Pring and Michael Walton, students working with Hammond, excavated, collected burnt wood for radio-carbon dating and started mapping the site. Hammond carried out a six-week field season at Cuello in 1976, concentrating on the temple pyramid within the platform. Several burials and cache (offering) vessels were unearthed, all dating to the Preclassic or Formative Period and evidence was found of the destruction of ceremonial buildings by fire and demolition.

From 1978 to 1980 Hammond focused on obtaining information about the Early Formative community at the site. Deep stratified deposits buried by platform 34 were exposed and the surrounding area mapped and excavated to determine the extent and scale of the Early Formative settlement; microorganic material collected through flotation was sampled to get information on diet.

Using radio-carbon and stratigraphic methods Hammond confirmed the early dates he had postulated in 1973 and extended the calendar back from 1500 B.C. to 2500 B.C. Work was not resumed until 1987, when Hammond returned to investigate problems outstanding from previous seasons. Using new techniques he collected small carbon samples of maize for dating and excavated middens and some architecture to relate functions of some of the Middle and Early Formative structures. Again excavations focused on the once large platform, now called North Square. Complex Middle and Late Formative structures were encountered; excavations into earlier sequences have been left for future work.

Cuello is in an intensively utilized land area, the major structures lying within a cattle pasture. To prevent further destruction, buildings have been left under vegetation until further excavation and consolidation can be done.

Cuello is very near to and easy to reach from Orange Walk Town. The site is in the compound of the local rum distillery of the same name, about 4 miles from Orange Walk on the Yo Creek road. Taxis are available in Orange Walk Town. Since Cuello is on privately owned land, permission is needed to enter the site: during the week you must call Cuello Distillery during normal business hours at 03-22141.

Altun Ha, a major Classic Period center, is located 30 miles north of Belize City, near Rockstone Pond

Village, 6 miles from the sea, in the Belize District.

The entrance to the ruins is

approximately one mile from Mile 32 of the Old Northern

Highway. Although there is no public transportation to the ruin,

there are several travel and tour operators who can provide

service to Altun Ha.

Altun Ha, a major Classic Period center, is located 30 miles north of Belize City, near Rockstone Pond

Village, 6 miles from the sea, in the Belize District.

The entrance to the ruins is

approximately one mile from Mile 32 of the Old Northern

Highway. Although there is no public transportation to the ruin,

there are several travel and tour operators who can provide

service to Altun Ha.

Altun Ha, the most extensively excavated ruin in Belize, was a major ceremonial center during the Classic Period, as well as a vital trade center that linked the Caribbean shores with other Maya centers in the interior.

The ruin consists of two main plazas with some thirteen temple and residential structures. The "Jade Head", representing the Sun God, Kinich Ahau, was the most significant find during excavations. At approxmately six inches high and weighing nine is and three-quarter pounds, it is still to this day the largest carved jade object in, the whole Maya area.

To the Maya, it was a powerful southeastern trading post linking the Caribbean shore with the cities of the interior. Altun Ha reflects the far reaching influence of Teotihuacan, now Mexico City. Protoclassic grave goods, particularly a distinctive green obsidian and the ceramics, are directly traceable to Teotihuacan.

Tikal, a Classic lowland center, is contemporaneous and of the same general nature as Altun Ha. There are similarities in ceramic motifs and dedicatory offerings. Dr. David M. Pendergast, who headed the major excavations, named the site Altun Ha or "rockstone water" after Rockstone Pond which was mistakenly thought to be the main reservoir of the area. The government maintains the ceremonial courtyard of temples and palaces (groups A and B). Two hundred seventy-five unexplored ceremonial structures girdle the precinct as well as hundreds of mounds that once housed 10,000 people over an area of two square miles. Altun Ha shows a population density 85% greater than that of residential Tikal. This figure is a reflection of the terrain which is dotted with swamps affecting the settlement pattern. There is a lack of consistency in building orientation which is in direct contrast to Tikal. There also is little consistency in the type of structure distribution in each zone, and structure groupings and various zone characteristics are unlike one another.

The reservoir southwest of the ceremonial complex is known as Zone E. It was densely populated probably due to the principle water source located there. Causeways were constructed to provide access across swampy areas. Although the area is miserable for farming, studies of ridged field systems and other intensive agricultural practices seem to indicate that the Maya were able to support themselves in areas of low agricultural potential.

Late Classic Altun Ha showed a sharp decline in population unlike the nearby center Lamanai, which continued to be occupied into the Conquest Period. Late Classic architectural attitudes at Altun Ha were exuberantly liberal in contrast to the strict Lamanai building type. However, offerings show less diversity than at Lamanai, and are more like those at Tikal. Group A, the main ceremonial center, remained in use throughout the Late Classic, falling into disuse except as a residential area during the Post-Classic Period.

This Classic Period ceremonial center was important as a trading center and as a link between the coast and the settlements of the interior. Trade goods traceable to Teotihuacan near Mexico City, have been found at Altun Ha. The unique jade head sculpture of Kinich Ahau (the Maya sun god), the largest known well carved jade from the Maya area, was discovered at this site. The site was named after the village it is situated in Rockstone Pond, the literal Maya translation meaning "stone water"'.

Altun Ha is located about 31 miles north of Belize City off the old Northern Highway near Rockstone Pond Village. No regular public transportation is available, although Maskall Village transport trucks run several days of the week from Belize City. Accomodations are available at Maskall Village, 8 miles north of the site, from Maruba Resort about 10 miles in the same vicinity or at Hotels in Belize City and Orange Walk Town

Historical context

Altun Ha exhibits such remarkable features that it is

regarded as one of a group of sites along the Caribbean

coastline which together constitute a distinctive cultural

zone. The erection of stelae was apparently not part of

ceremonial procedures at the site. Neither are the tombs

in the dominant structure, the Temple of the Sun God,

those of dynasties of warlords: instead they are burials

of priests. Moreover, as archaeologist David Pendergast

puts it: "A unique form of sacrifice became the focal

point of activity on (structure) B-4; atop the altar,

offerings of copal resin and jade objects, including

beautifully carved pendants which had been smashed

into small pieces, were cast into a blazing fire. In the final

such sacrifice on each of the altars, just prior to the

covering of the building with later constructions, the bits

of jade, resin, and charcoal were scattered over the floor

surrounding the altar, and left as a sort of fossilized

ceremony, to be discovered some 1300 years later.

The site

Altun Ha is a particularly rich ceremonial centre with two main plazas in its ritual precinct. Thirteen structures surround these plazas; the tallest, the "Temple of the Sun God" / "Temple of the Masonry Altars" rises 18 metres (60 ft.) above the plaza level. Located 8.3 km. (5 miles) west of Midwinter Lagoon and 12 kin. (7.5 miles) from the sea, Altun Ha covers an area of 2.33 sq. kin. (1.5 sq. miles) including an extensive swamp north of the site.

The existence of Altun Ha was first recognized by A.H.

Anderson who, in 1957, followed up a report of some questionable mounds in the area. In 1961 W.R.

Bullard examined portions of the site which was then

ignored until 1963 when villagers' quarrying work

uncovered an elaborately carved jade pendant. This

discovery triggered events which culminated in the first

long-term, full-scale archaeological project in Belize -

David Pendergast's 1964-1971 excavation.

Artifacts from that series of excavations, which were

carried out under the auspices of the Royal Ontario

Museum, were subject to the previous antiquity laws,

such that half the artifacts recovered went to that

Museum.

From 1971-1976 Joseph Palacio did restoration work on

Altun Ha, as did Elizabeth Graham in 1978. The site was

the second in Belize to be partially cleared and

consolidated for tourism.

Of cardinal importance to the development of Altun Ha

was the great water reservoir, now somewhat

unromantically called "Rockstone Pond". This reservoir

has minimum dimensions of 4,700 sq. metres (50,500 sq.

ft.) and maximum dimensions of 6,643 sq. metres (71,500

sq. ft.). The bottom is lined with yellow clay, forming a

fairly regular basin. At the south end water containment

was effected by a dam of stone and clay, which was

probably erected in order to convert a small pond into a

major reservoir and to prevent outflow into the marshy

area further south. The presence of large, angular stone

blocks around the edges suggests that quarrying was

carried out, perhaps with the aim of enlarging the water

storage capacity. The reservoir probably never ran dry

and this factor, together with the site's proximity to the

sea contributed to the selection of the site's location; its

extreme religious function remains unexplained.

Archaeological work

Locale and access

Altun Ha lies 31 miles north of Belize City on the old

Northern Highway and 37 miles from Orange Walk Town

on the same road; a two-mile feeder road connects the

site with the highway. The landscape around the site

consists of bush, plantations and orchards and although

the area to the east is swampy, the site's surroundings

have twice been used by film companies for their jungle

scenes.

Wildlife at the site includes opossum, various species of bats, armadillo, tamandua, squirrel, spiny pocket mouse, agouti, paca, grey fox, raccoon, coati, tayra, skunk and, formerly, an occasional tapir or whitetailed deer; more than 200 species of birds have been observed there, and a 9 ft. crocodile still lives in the water reservoir itself.

A series of typical Creole villages lines the road to Altun Ha, such that the interested visitor can experience Belizean culture past and present as well as its natural history.

No regular transport is available to the site, although

Maskall village transport trucks run several days of the week from Belize City. Accommodation is available in

and around Maskall, eight miles north of the site, or in

hotels in Belize City and Orange Walk Town. At the site

itself are restrooms, drinking water and a picnic area.

Related Links:

Xunantunich was a major ceremonial center during the Classic Period.

The site is composed of six major plazas, surrounded by more than twenty-

five temples and palaces. The most prominent structure located( at the

south end of the site is the pyramid "El -Castillo" (The Castle) which is 130

feet high above the plaza. "El Castillo", which has been partially excavated and explored, was the tallest manmade structure in

all of Belize, until the discovery of "Canaa" at Caracol. The most notable

feature on "El Castillo" is a remarkable

stucco frieze on the east side of the A-6 structure. Three carved stelae found at the site are on display in the

plaza. The name is Maya for "stone lady" and is derived from local legend.

Currently, additional

explorations and excavations are

being performed by Dr. Richard

Leventhal and the Department of

Archaeology, in an effort to better

understand the history of

Xunantunich.

This major ceremonial center is located on a natural limestone ridge, providing a panoramic view of the Cayo

District.

Xunantunich is located across the river from the village of San Jose Succotz, near the western border, and

can be reached by ferry daily between 8am and 5pm. Daily public transportation to Succotz is available.

Accomodations are available in San Ignacio Town 10 miles away, in Benque Viejo 1 mile away or at two

nearby resorts, Chaa Creek and El Indio Suizo.

Historical context

The name Xunantunich -Stone Woman- is of local but

relatively recent origin. But the classification of the site

as female has prompted some exotic metaphors,

sometimes from surprising sources: in the view, for

example, of Tennant Wright S.J., Ximantunich is a

"phallic temple".

In fact, there is no reason to believe that the Maya ever

classified their ceremonial centres by gender.

Nonetheless, Fr. Wright was correct in stressing the

sexual symbolism of the sacred structures. This in itself is

not new: the great majority of, if not all, religions focus on

the power to generate and re-generated -on fertility. But

what helps us to understand the stelae at Xunantunich

and elsewhere is their association with both the power to

reproduce and the warlords: since the stelae were both

phallic and commemorated the warlord's victories, the

warlords and their ancestors were being portrayed as the

source of fertility for all Maya, including of course the

peasantry who, as maize producers, were the real source

of the group's fertility.

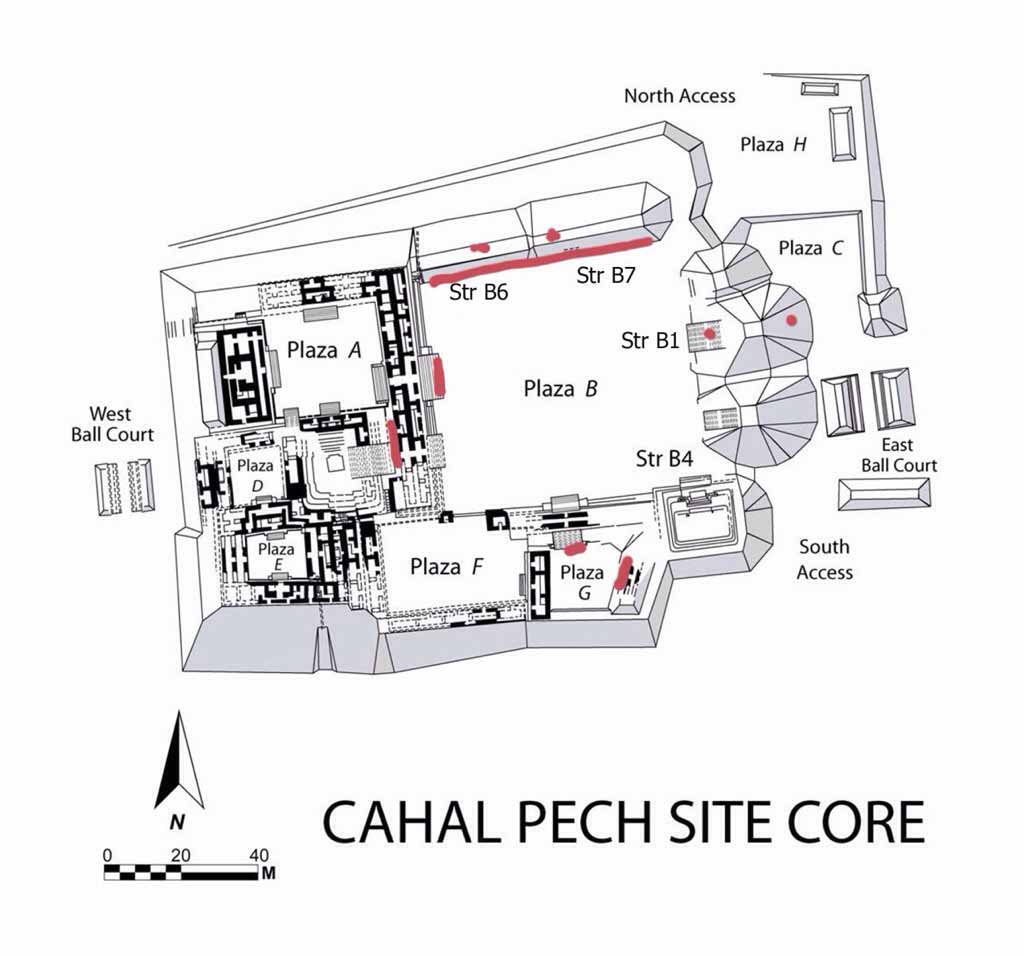

The site

Xunantunich is a Classic Period ceremonial centre.

Restricted in space, it occupies only 300 sq. metres (325

sq. yards) with elite, middle- and working-class

residential structures stretching a few kilometres into the

surroundings. The structures of the ceremonial centre

itself are labelled "Group A" on the diagram; most are

thought to be temples; plazas are labelled in Roman

numerals. Group B is a residential group occupied from

the 7th to the 10th centuries. Group C structures may

comprise a ball court (C-2 and C-3).

Attention naturally focuses on Group A, for structure A-

6 rises 40 metres (130 ft.) above the level of the plaza.

About 10m. (35 ft.) up the north side of the structure

there is a wide terrace: it is now covered with debris and

earth, but at one time it had buildings standing along its

outer edge. The wide stairway that you see about one-

third of the way up the front leads up to this terrace.

Above the terrace rises a high platform, now covered

with earth and plants. On top of this platform are two

temples, the upper of which is the later. The Maya built

this by covering the lower temple and making a platform

out of it. The reason that you see both temples revealed

is that archaeologists have cleared the debris and earth

from both, exposing them for us, but not as they would

have been seen in ancient times.

The lower temple is well known for the frieze -the band of

stucco decoration- which at one time extended above the

doorways around the entire building, but which has been

preserved only on the east side; it wasrestored in 1972.

The carved elements are signs. The mask with the "big

ears" and ear ornaments represents the sun god. Next to that is the

sign for the moon, and there is a border of signs which

stand for Venus and the different days. We do not know

who the headless man is, but he was deliberately

"beheaded" by the Maya for some reason in the past.

Archaeological work

We would be likely to learn considerably more about the

turbulent times which terminated the Classic Period were

Xunantunich to be systematically excavated. This has

never been done.

Early investigations of Xunantunich were conducted in

1894 and 1895 by Dr. Thomas Gann, a British medical

officer, who later published his discoveries from the site.

In 1904 Teobert Mahler of the Peabody Museum of

Harvard University took photographs and produced a

plan for structure A-6. Upon his return in 1924, Gann

uncovered and removed vast quantities of burial goods,

as well as the carved hieroglyphs which encircled altar 1;

we presently have no knowledge of the whereabouts of

those glyphs.

Work here was originally begun in 1938 by the "Father of Maya Epigraphy," J. Eric Thompson, who investigated two structures northwest of the main plaza. Referred to as Group B, these are Classic middle class units. The ceramics he extracted have been set in a sequence for the Late Classic Period which remains chronologically correct.

In 1950, Linton Satterthwaite of the University of Pennsylvania, conducted small excavations on the highest building in the main plaza, the A-6 structure. It is a Classic building of large, beveled vault stones, faced with a stone veneer. The stucco frieze he discovered on the upper zone of the east facade, an earlier element of A-6, depicted glyphy which make reference to the 584 day cycle of four periods in which Venus shifts from its position as morning star to evening star. There is a headless bust before a niche in the frieze which is probably a secondary addition. Further excavations exposed a deity mask and two bands of glyphs which associates it with the most prominent celestial bodies / deities -- the Moon, Venus and the Sun. The mask is centered above a doorway with bands containing sky glyphs. Inclusive is a large stylized crescent moon glyph. Also uncovered was. the figure of a man, down on one knee carrying a set of glyphs. In 1959, the rest of the frieze was cleared by A.H. Anderson, then Archaeological Commissioner of Belize. He also built an access road and completely cleared the ceremonial center of jungle growth.

From 1952 to 1957, Michael Stewart conducted periodic excavations of the main plaza, predominantly structure A 2. This two room building has a plain stela set at the foot of the stairway around which a small temple was built at a later date. Uncovering A-3 and A-4, Stewart learned that there were originally separate structures with basal moldings resembling those at Uaxactun, approximately 45 miles northwest. He also cleared the A1 stairway.

In 1959, Euan Mackie of Glasgow University, in conjunction with Cambridge University, cleared A 11, a vaulted palace and A-15, a smaller residence, as well as other buildings around the main plaza. It appeared to him that both A-11 and A-15 collapsed due to human destruction (buildings were frequently razed before new ones were built), or more likely by earthquakes (there are indications of fault lines running through the district which could theoretically wipe out a town). There were huge ceiling vault stones which had collapsed, crushing the pottery (dated to the Classic Period) inside. Though there are two debris mounds in plaza B indicating an initial clean-up and an obvious reoccupation of A15 during the Post-Classic, the buildings were never reconstructed. Mackie believed this could be due to the hierarchy being unable to organize work crews due to the people's loss of faith in their leader's apparent lack of god/earthquake control. He believes Xunantunich's fall triggered the decline of San Jose and Uaxactun continued. According

to construction evidence at San Jose. and Uaxactun, it is believed that the Classic Period continued for a short time after the collapse and then entered a brief period of decline.

Building continued at these two sites until they were suddenly and inexplicably abandoned. Therefore, the Xunantunich disaster and Post-Classic transition into the final stages would have been between 890-900 A.D., with the abandonment of San Jose and Uaxactun shortly afterward.

In 1979, evidence of looting in Group B-5 spurred a salvage project conducted by Dr. David M. Pendergast and Elizabeth Graham of the Royal Ontario Museum. Rescue archaeology is always a disappointing task as the damage done by looters is irrevocable. All information which could be gathered from burials, critical associations between objects, and an artifact's exact position, or the small fragile objects is lost forever. In the eagerness of an individual's desire to own a unique specimen or to make a buck, the history that gives an object its worth is destroyed. In this case, it is obvious that the looters did not understand the relationship of B-5 to the rest of the structures for they tunneled into the back corner of the structure instead of the side facing the plaza. From their backdirt, which they did not take the time to move, the salvage project recovered a 7th century A.D. censer with a human face. We have an object; its relevance is lost. The burial was completely destroyed The information gained shows that B-5 is a small, unadorned platform faced with stone. A broad stairway is on its front with a low extension at the side which connects it with another Group B structure. There are no chambered buildings or wall remains to indicate that the platform supported a stone structure. This means there was probably a perishable structure atop, but the poor surface condition makes location of postholes impossible. Twelve inches below the platform, a shallow grave was capped by stone.

An adult female was laid with her head to the south. The extensive dental work indicates that this person had a great rank or status. Her upper incisors were notched. All her lower incisors were notched in the center occlusal surface. There was only one associated artifact, an elaborate ceramic whistle. The grave is dated to the Late Post-Classic Period. There are indications of an earlier structure which had been characteristically razed. In honor of the new construction, an offering of a unique censer/strainer with a burnt post-fire stucco wash had been placed within the earlier structure. Ceramic vessels date to the Late Classic Period. The last construction phase of B-5 was in the Terminial Classic Period.

In 1938 the British archaeologist J. Eric S. Thompson

excavated a middle-class residential group of buildings

(Group B) near the site centre and in 1949 A. H.

Anderson rediscovered the remains of the stucco frieze,