Alone in the Caribbean

CHAPTER XI.

WE MAKE OUR BEST RUN.

WE LEFT the beach in a dead calm. The sun was nearly an hour above an horizon of trade clouds and even as I rowed I could see the wind that was coming begin to darken the water in patches to the eastward. In half an hour the wind caught up to us and soon after I set sail. We were scarcely free of Guadeloupe when the canoe began to move with the first light breaths, over a long easy swell. Montserrat was a hazy blur on the horizon, and I should have to look sharp lest I miss it.

For a while I held directly for the blur, but as the wind freshened it began to work into the south'ard and I shifted my course till I was running wing and wing with the island two points to weather. I did this so that later in the day I would not have a hard wind and a heavy sea directly abaft -- the most ticklish and nerve-tiring condition for canoe sailing. The wind was increasing steadily and I knew I was in for half a gale -- and a good run. I also knew that while it was necessary to make as much speed as possible, I should have to keep a sharp eye on my gear, for if anything crippled my rig for windward work I was in for an adventure on the Caribbean. This wind held for a week and were I blown clear of Montserrat there would be no choice but to keep on with some sort of rig up till I struck Saint Croix, one hundred and seventy-five miles away.

If ever at any time on this cruise, I was now sailing along the thin edge of things. Although it was a second quarter that had come in soft, it seemed that a fifth day had slipped in somehow for the weather was on a rampage. We were nearing the end of the regular trade season and might expect our almost infallible weather signs to break down. I found that my barometer showed but little variation during the time I was in the Lesser Antilles and only kept tabs on it in order to note the decided drop which might indicate the approach of any weather more severe than the ordinary blow.

As far as I could see to windward, north and south, squalls were now chasing down as though there were two conditions of wind ; one a stiff breeze and the other a series of squalls moving independent of and through the first. The canoe was traveling so fast -- we were making a good six knots -- that I could easily dodge most of the squalls by tacking down the wind like a square rigger. Once I was actually running off on the port tack WSW while the course from Deshaies was NW1/4W. There was no harm in being thrown off my course to the south and west for it ultimately served to place Montserrat all the more to windward.

When the wind which was blowing from east-southeast finally declared itself a young gale, I found to my great relief that I had worked my way so far to the westward that my course for the island was now a little better than NWbN. Instead of having to run within one point of being dead before the wind our course was now two points farther to windward. Nearly every sea was breaking and we were making a continual succession of toboggan rides, the breaking seas at times carrying us up the back of the sea ahead so that we were actually traveling a little faster than the waves themselves. This surf-riding soon became a regular habit and I was forced to reef the mainsail and mizzen lest the Yakaboo turn end for end. We now slowed down to a more reasonable speed.

One might imagine that at a time like this I would have little chance for observation and yet with my senses alert to their highest efficiency there was very little that escaped me. My eyes wandered on a continual circuit from the compass in my cockpit into the belly of my mainsail, up the mast and down again to the seas about me. Then we swung on a quick circuit through a hundred and eighty degrees from the seas under our bows to the squalls astern, taking in the skies on our return.

It was on this mind panorama that I saw more distinctly than at any other time the manner in which these islands gather moisture from the trade clouds. For a time after we had left Deshaies, Montserrat moped mist-wrapped on the horizon. Then slowly the heat of the morning sun prevailed and the island became more and more definite in outline till it at last showed clear and distinct -- a volcano on the horizon. The island is made up of two peaks but from my position they were almost directly in line so that I saw only the outline of the southernmost and larger, the Souffrière.

The wind was then blowing lightly and the sky was clear of clouds except in the east where they were advancing in droves with the wind before the sun. The trade overtook us first and then came the clouds, fleecy and bulging, like ships before the wind, each with a squall under it. I watched a small cloud, one of the first of the van, approach the peak with unslackened speed till it lodged against the mountainside two thousand feet above the sea, where it came to a full stop. It seemed almost to recoil a bit. Then it slowly embraced the peak and more slowly began to draw away again to the westward. When it was finally clear of the island I saw that it had lost half its bulk. Montserrat had taken her toll in mountain showers.

For a space the peak was again clear in outline, two volcanic curves that came out of the sea to meet three thousand feet above. Next a large stately cloud, a ship of the line among the others, enveloped the peak and came to a stop. There it hung and diminished in size till it was reinforced by another cloud and for the rest of my run the upper third of the island was hidden in a cloud cap, which diminished and increased in volume like slow breathing.

The wind seemed to be continually freshening and I found that although I had reduced my sail area by nearly one-half, I was again catching up to the seas ahead and tobogganing. I had moved the duffle in my cockpit as far aft as I could and sat on the deck with my back against the mizzen mast. Just above my head I lashed my camera -- the most precious part of my outfit. At the first indication of broaching-to I would take hold of the mast and force her over on her weather bilge till she was almost before the wind. Then I would let her come up to her course and hold her there till she took the bit in her teeth again when I would have to pry her back as before.

My blood was up and I told her that she could turn end for end if she wanted and tear the rig out before I would take in any more sail. A bit of anger is a great help at times. Another time, when I go canoe cruising on the sea, I shall carry a small squaresail and a sea anchor that I can readily trip. In spite of all my efforts it seemed that we should be forced to weather of Montserrat and that I should have to run off for a while to the southeast. But we were sailing faster than I suspected and at last fetched up abreast of the southern end of the island and about a quarter of a mile off shore. Then I brought her into the wind and hove-to with the reefed mizzen and let the wind carry us into the calm water under the lee of the island.

I looked at my watch and found that it was just eleven-thirty. We had made our last long jump, the most exciting of all our channel runs in the Caribbean. We had covered thirty-five miles in five hours and ten minutes. We had sailed thirty-three miles in four hours and forty minutes -- our average speed had been a little more than seven miles an hour. For some time, however, after I had made sail our speed was not much more than five miles, and I believe that the last nine miles had been covered in an hour, with fifty square feet of sail up! Except in a racing canoe I had never sailed faster in a small craft than on this run.

The wind, eddying around the end of the island, was carrying us directly along shore and I lowered my mizzen while I ate my luncheon. It was pleasant to drift along without thought of course and to watch the shore go by at a three-mile gait. I had just settled myself comfortably in the cockpit when I noticed a native who had come down to the beach waving his arms frantically. That we drifted as fast as he could walk along shore was good evidence that the wind was blowing strongly. I learned afterwards that he thought me to be the sole survivor of a fishing boat that had been lost a week before from Nevis. She was never heard from. After I landed at Plymouth I was told that a sloop had been dismasted that morning in the roadstead.

At the time it was a genuine source of satisfaction, not that I was happy in the ill luck of the sloop, but I regarded this as proof of the sturdy qualities of the Yakaboo. One must, however, always be fair in such matters and it is only right for me to say that after further acquaintance with the sloops of the Lesser Antilles it is a marvel to me that they stand up as well as they do. The credit does not rest with the Yakaboo but rather with the freak luck of the West Indian skipper. God, it seems, has greater patience with these fellows than with any other people who have to do with the sea -- I have purposely avoided calling the natives of the Lesser Antilles sailormen.

There was not much in Montserrat for me. Thirty miles to the northwest lay Nevis and St. Kitts -- stepping stones to St. Eustatius and Saba. A nearer invitation than these was Redonda, a rounded rock like Diamond off Martinique which rose almost sheer to a height of a thousand feet out of deep water with no contiguous shoals, a detached peak like those of the Grenadines -- a lone blot with Montserrat the nearest land, eight miles away. On the 10th of November in 1493 Columbus coasted along Guadeloupe and discovered Monserratte, which he named after the mountain in Spain where Ignatius Loyola conceived the project of founding the Society of Jesus. "Next," says Barbot, "he found a very round island, every way perpendicular so that there seemed to be no getting up into it without ladders, and therefore he called it Santa Maria la Redonda." The Indian name was Ocamaniro.

It was on the morning, when I was loading the Yakaboo for the run to Redonda, that I came as near as at any time to having a passenger. As I was stowing my duffle, there was the usual circumcurious audience, beach loafers mostly, with a transient friend or two who had come down early to see me off. The forehatch was still open when the parting of the crowd proclaimed the coming of a person of superior will, not unaccompanied by a height of figure, six feet two, strong and raw-boned, the masculine negress of the English islands. She carried a large bottle of honey and a jar of preserved fruits.

"My name is Rebecca Cooper," she said by way of introduction, "an' I cum to ask if you take a passenger to Nevis wid you."I looked at the cockpit of the Yakaboo and at her tall figure.

"Oh, me seafarin' woman, me no 'fraid. Oh, yas, I been Trinidad -- been aal 'roun'!""I'm sorry," I said, "if you're to be the passenger the skipper will have to stay ashore."

"Das too bad. Annyway I bring you a bottle of honey an' some Jamaica plums an' cashews."

I stowed the bottle and the jar in exchange for which she very reluctantly took a shilling. She lived somewhere up in the hills and having heard fantastic tales of the Yakaboo she had come down to see the canoe and its skipper with her offering of mountain honey and preserves. It was unselfish kindness on her part and she only took the shilling that she might buy "some little thing" by which to remember me. There are many like these in the islands, but they are scarcely known to the tourist -- sad to relate.

While Rebecca Cooper was silently examining the canoe, I took out the clearance paper which the Collector of Customs had given me the day before. It read as follows :

*****MONTSERRAT

Port of PLYMOUTH.THESE are to certify all whom it doth concern, that F. A. Fenger master or commander of the Yakaboo, burthen 1/4 tons, mounted with __ guns, navigated with __ men Am. built and bound for Nevis having on board Ballast & Captain hath here entered and cleared his vessel according to law. Given under my hand at the Treasury, at the Port of Plymouth, in the Presidency of Montserrat, this 18th day of May, one thousand nine hundred and eleven.

EDWARD F. DYETT

1st Treasury Officer*****

It was the "Ballast and Captain" that made me think. My outfit -- not perfect as yet, but still the apple of my eye -- was put down as "Ballast" and to add ignominy to slight I was put down under that as "Captain." I dislike very much this honorary frill -- Captain -- it is worse than "Colonel."

The wind was light from the southeast and we -- the Yakaboo and I, for we left Rebecca on the beach with the crowd -- slipped off with eased sheets at a gentle gait of three miles an hour.

The early settlers of Montserrat and Nevis were largely Irish. Strange to say, among the first Europeans to see the West Indies were and Englishman, Arthur Laws or Larkins, and an Irishman,m William Harris of Galway, who sailed with Columbus. We are inclined to think that the crews of the Admiral's fleet were made up wholly of swarthy Portuguese, Spaniards, and Italians. Churchill, in speaking of Redonda, says that most of the inhabitants were Irish -- but what they could find for existence on this almost barren rock with its difficult ascent is hard to understand. It is true that Redonda proved to have a considerable commercial value, but not until 1865 when it was found that the rock bore a rich covering of phosphate of alumina. The rock is not nearly exhausted of its rich deposit, but I was told in Montserrat that I should find a crew of negroes in charge of the company's buildings.

One must always take the words of early explorers -- as well as modern ones -- with a grain of salt in regard to the wonders of nature, but when Barbot called Redonda a "very round island, every way perpendicular so that there seemed to be no getting up into it without ladders," he did not exaggerate. When I lowered the sails of the Yakaboo under the lee of Redonda, I saw that the sides of the rock rose sheer out of the water like the Pitons of Saint Lucia, except for one place where a submerged ledge supported a few tons of broken rock which had tumbled down from the heights above. This could hardly be called a beach and it was no landing place for a boat.

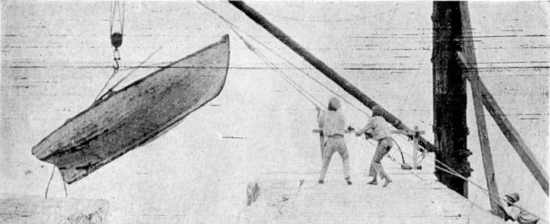

Built up from this ledge of debris was a concrete pier which stood some ten feet above the water and was surmounted by a wooden cargo boom. Anchored in the rock near the pier was a steel cable that ran up like the thread of a gigantic spider to a point some four hundred feet above, where I made out a sort of staging. I rowed close to shore and shouted, but there was no answer. Then, thinking that I was too far under the cliff, I rowed off a bit and began to fire my thirty-eight-forty. A voice from somewhere up there shouted down to me but what it said I could not understand. I located two figures busy on the staging and presently a miner's bucket began to slowly slide down the cable. There was something novel in this; sailing up to an immense rock in the sea, firing off a revolver as a signal to natives I had never seen before, and having a bucket lowered for me from a height of four hundred feet.

While I was watching the descending bucket a boat with four men in it came from around the end of the rock. The sea being smooth they were fishing on the weather side of Redonda and when they saw me they came post haste for they had been expecting me. They rowed alongside and I put aboard the duffle I should require for the night. Then we fastened the painter of the Yakaboo to a large mooring buoy used by steamers when taking on their cargo from lighters towed up from Montserrat when the occasion requires. I very carefully examined the buoy with its seven-eighths chain and asked the men if it would hold the canoe in case of a blow.

"Shur! an' it's th' same moorin' we use fer th oiland whin a hurricane is blowin'," said one with a brogue as broad as any just over from the Isle.The speaker was Frederick Payne, as pleasant a native as I have found in the islands, who if you put him in another room and heard him talk you would wager the soul of your maternal grandmother against a thrupenny bit was no other than a red-whiskered Irishman.

Hauling in the boat.

Hauling in the boat.

The capstan.

The bucket.

The canoe made fast, we rowed ashore and clambered up the iron ladder on the face of the pier. The boom was swung out, tackle lowered and the boat hoisted inboard like a piece of cargo. The bucket which had come down with a load of phosphate, we emptied and climbed aboard for our aerial ride The winch was started and we were slowly hauled up the cable which follows a ravine-like cleft in the rock. On either side was a scanty growth of scrub brush and cactus which seemed to grow for the sole purpose of giving perches to the noddies and gulls that eyed us from a fathom's length or two with the all-seeing idle curiosity of a cash girl of a dull afternoon.

Little by little the Yakaboo diminished in size till she looked like the weak dash of an exclamation point with the buoy for an overgrown period. The sea was sinking away from us. I took out my barometer and we watched the needle while it swung from "Fair" to "Change." Finally the needle stopped and we were hauled on the staging by the two sweating natives who had wound us up. By an easy path, we climbed three hundred feet more to the company's buildings.

What an eagle's nest from which to look down upon a world of sea! Montserrat was a near neighbor, high Nevis not much farther off brought out of the place queer thoughts of school days when Hamilton was a mere bewigged effigy on the glossy page of a history book. What right had he to be born down here in the Caribbean? There was Antigua to windward of the arc of our cruise; what right had she and Nevis to know Nelson whom our young minds inferred spent his entire life at Trafalgar and the battle of the Nile? Edging out from the weather shoulder of Montserrat lay Guadeloupe in a shroud of mist as though keeping to herself some ferment of a modern Victor Hugues. But the redundant thought was always of the riches that have been in these islands and the extraordinary selfishness and sordidness that have been the motives of nearly every act since the discovery of the West Indies by Columbus.

We were too high for the glare of the sea and I wandered about through the whole delightful afternoon on the top of the rock to descend at sunset to the enclosed verandah of the manager's house where I satisfied a righteous appetite with a roasted chicken of Ethiopian-Irish upbringing.

In the morning I was lowered from this giant's stepping stone and was once more cockpit sailing, in a light breeze, for Nevis. Except for the distant sight of a goodly "gyaff topsail" on the first day when I skirted the Grenada shores, I had seen no indications of large sharks. What had at first been a haunting bugaboo had now become a forgotten possibility. We were approaching the banks which lie to the southward of Nevis and I sat on my blanket bag, bent up behind me like a cushioned easy chair with a lazy-back.

There was just enough breeze to allow me to lean with my elbow on the weather deck. Sharks were as far removed from my thoughts as the discussion of the Immaculate Conception -- I believe I was actually deciding that my first venture upon escaping the clutches of the chosen few who guard our national customs would be a large dish of ice cream which I would eat so rapidly that it would chill the top of my head and drive from it forever the memory of the calms of Dominica and Guadeloupe. My mind was fondling this chilly thought when suddenly the flash of a yard of rainbow under my bows announced the arrival of a Dauphin, or, as they called them in the days of Labat, a Cock Dorade. By the shape of its square-nosed head I could see that it was the male of the species. I have often wondered whether this was not the dolphin of the dying colors -- it surpasses even the bonito in the marvellous changes in its hues when expiring. These fish are common near the northern coast of Martinique. Père Labat says that in order to catch the dorade without bait one must troll with a fly made of two pigeon feathers on each side of a hook and smeared with dog grease. I watched him leisurely cruise for a while back and forth under the bow when suddenly there was a mighty swirl under the nose of the canoe and I saw the greyish white torpedo form of a huge shark heave after him. The dauphin was not to be caught unawares -- the Lord knows how long Mr. Shark had been watching him from under the shadow of the Yakaboo -- and the pair tore away through the sea, the shark a lagging second. After a hopeless dash the shark gave up the chase.

I watched the dorsal fin make a wide circle to windward and then coming up from astern he settled down for a comfortable loaf under the canoe where he could again lie in wait for a careless dauphin that might happen along. I leaned over and watched him as he hung, indolently, just to leeward of the tip of my centerboard. He seemed almost as long as the Yakaboo -- once when he drifted a little off-side, I got his measure, his length reaching from the forward point of the canoe's shadow to the upright line of the mizzen; by this he must have been a little over twelve feet in length. If he were not as "big 'roun' as a barril" he certainly would have been a good armful had I jumped overboard to embrace him, -- but I had no such intention. He must have been too slow and ponderous to feed on such swift fish as the dauphin unless he caught one by surprise as he had tried to get this one from the shadow of the canoe.

No wonder these fellows become desperate at times and go in packs like hungry wolves to some whale pasturage where they can drag down their cattle by sheer force of numbers after the manner of their land relations. I had no reason to believe he would trouble me unless I was foolish enough to throw something overboard or otherwise attract his attention by leaning too far out to look at him. A sly peek over the edge of the gunwale was enough and I made that with my arsenal ready. What he thought this could be sailing so slowly above him with a belly like a fish and a fin that did not scull and two white wings sticking up into the air from its back, I don't know, for I am as yet unfamiliar with the working of a shark's mind. Had he known there was a tasty scrap (pardon this subtle bit of self-flattery) only three feet away should he choose to butt that stiff fin, his actions might have been different.

I watched his wicked pig eyes but he did not seem to look up or take notice of the canoe. He merely hung there in its shadow, an almost imperceptible flexation of his body and a sculling of his tail being sufficient to move him along at three knots an hour. We were scarcely two miles from Redonda when he had come back from his dash after the dauphin and from that time for over ten miles, till we were well within the Nevis bank, he hardly varied his position a foot. I have somehow or other always associated the presence of sharks with calm weather and oily seas. The story books always have it so. In the West Indies the shark is more in evidence during the calms of the hurricane months than at any other time. On this account the French call him requien which is a corruption of requiem. Rocheford says, "Les François & les Portugais luy donnent ordinairement ce nom de Requiem, c'est à dire Repose, peutetre par ce qu'il à accoutumé de parôitre lors que le tems est serain & tranquille . . ." (The French and the Portuguese usually call it Requiem, that is to say Repose, perhaps because it usually appears when the weather is serene and tranquil.) At last he slipped away, a gruesome shape, to cruise about ghostlike on the shoals. I almost felt lonely after his departure -- his absence was like that of a sore tooth which has been pulled out.

The shark took with him what little wind there was and I rowed around the corner of Nevis to its port of entry, Charlestown. Nevis runs up into a single peak, the lower slopes sweeping down to the sea like a train checkered with sugarcane plantations. The island seems more wind-swept than Montserrat; it has a fresh atmosphere quite different from all the rest of the Lesser Antilles -- still it is one of the oldest and was settled in 1608 by Englishmen from St. Kitts. To me there is a singular fascination in going ashore in a place like this and coming upon some old connection with the history of our own republic. I had purposely loafed on my way from Redonda so that I could land in the cooler part of the afternoon.

As soon as I had shown my papers to the harbormaster, he said, "Can I do anything for you?"

"Yes. Show me the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton."It was like asking for the village post office in some New England seacoast town. A walk of two minutes along the main road brought us to the place where I took a photograph of a few ruined walls. Here I could gape and wonder like any passing tourist and reap what I could from my own imagination. They tell me that a famous writer of historical romance once spent a day here to absorb a "touch of local color." An admirable book and written in a style which will bring a bit of history to many who would otherwise be more ignorant of the heroes of our young Republic. It is history with a sugar coating but the "touch," I am afraid, is like that artificial coloring which the tobacconist gives to a meerschaum that is to become a pet. In all these islands there is no end of "atmosphere" to be easily gotten, but what of the innermost history of these places?

Nevis has always been a land of sugar, open country and fertile and in its time wondrously rich -- the ruins of old estates like that of the Hamiltons show that -- and in secluded places such as the little village of Newcastle on the windward side with its top bay, extremely picturesque. But in these places one must of necessity scratch around a bit and get under the top soil of things. What about the camels that were brought here from the East to carry cane to the mills? Who brought them here and when? Did the young Alexander know the sleepy-eyed, soft-footed beasts? There were one or two on the island as late as 1875 and I talked with a lady who as a small child used to be frightened at their groanings as they rose, togglejointed, from the roadway beneath her window. To learn the intimate history of these islands one must first visit them for acquaintance sake and then go to Europe and dig up stray bits from letters and manuscripts sent from the islands to the old country. Of papers and correspondence there is very little to be found here and it is at the other end of the old trade routes that one must search.

I left Nevis on a hot calm Sunday morning for Basse Terre, the port of St. Kitts. The row was twelve miles and the calm hotter than that of Guadeloupe. There was no perceptible breeze, just a slow movement of air from the northeast -- not enough to be felt -- a sluggish current that stranded a ponderous cloud on the peak of Monkey Hill, its head leaning far out over the Caribbean where I rowed into its shadow. When I was still half a mile from the town I stood up in the cockpit and took off my clothes. After I was thoroughly cooled I enjoyed a shower bath by the simple expedient of holding one of my water cans over my head and letting the water pour down over my body. Then I put on my "extra" clothes. They were extra in that they were clean. The shirt was still a shirt, for there is no alternate name for that which had degenerated into a mere covering for one's upper half, but the trousers were pants. They were clean; I had done it myself on the deck of the Yakaboo. Some day when I build another canoe I shall corrugate a part of the forward deck so that I can cling the better to it when I am trying to get into the hatch in a seaway and also so that I can use it as a rubbing board when there is washing to be done.

The shade of this cloud was something extraordinary. At first I thought there would be a heavy downpour of rain but the air was too inert and the cloud hung undecided. like most other things West Indian. For the first time in four months I could take off my hat in the daytime! I enjoyed this shade while I could and I ate my luncheon, the canoe drifting slowly northward on the tide. It was just the time and the place for another shark and I thought of my friend of the Nevis bank. I saw no fish and threw out no invitations and when I had had my fill I rowed into Basse Terre where I was received by the fourth unofficious harbormaster I had yet encountered.

But we shall not be long in St. Kitts, or Sinkitts as the authoress puts it by way of a little impressionist dab of "color." I found some interesting old newspapers in the cool library of Basse Terre where I spent several days reading the English version of the war of 1812. "Now!" I promised myself, "I shall see something of the island to which the Admiral gave his own name." But promises on a cruise like this, however, are not worth the wasting of a thought upon.

CHAPTER XII.

STATIA -- THE STORY OF THE SALUTE.

DON'T WASTE your time hâre," he said in the swinging dialect of the northern islands, "you will be among your own at Statia and Saba." I had met this Saba man on the jetty, Captain "Ben" Hassel of a tidy little schooner, ex-Gloucester, and he told me of the Dutch islands and their people. He was my first breath of Saba and my nostrils smelt something new.

Saba had been a love at first sight for I had already seen her at a distance from the deck of the steamer as we had passed southwards in January. The Christmas gale which had chased us down from Hatteras passed us on to that more frolicsome imp of Boreas, the squally trade on a "chyange ob de moon" day. It was the same Captain Ben's schooner that I had watched running down for the island under foresail. Through the long ship's telescope I had made out the cluster of white houses of the Windward Village, plastered like cassava cakes on the wall of a house, but as I came to know later, nestled in a shallow bowl that tipped towards the Atlantic. Although we were within the tropics, it blew down cold and blustering with an overcast sky more like the Baltic than the Caribbean. I did not then know how I should come to long for just such an overcast sky to shut off for a few hours that blazing ball of fire known to us of the North as the smiling sun. His smile had turned into a Sardonic grin. As Saba began to grow indistinct, the sharper outlines of Statia had brought me to the opposite rail and with hungry eyes I swept the shores which were all but hidden by the obstinate rain squall that had come down from the hills and was hanging over the cliffs of the Upper Town as if to rest awhile before starting on its weepy way westward to vanish later in the blazing calm of the Caribbean.

And that is why you shall hear nothing of St. Kitts for the day after I spoke with Captain Ben, I was again in the Yakaboo. The offshore wind that helped us up the lee of St. Kitts carried with it the sweet rummy odor of sugarcane that kept my thoughts back in the old days. Then, as we were well up the coast, there came another odor, a mere elusive whiff of sulphur, that went again leaving a doubt as to whether it were real, and my thoughts were switched to the formidable Brimstone Hill, now towering above us inshore, shot some seven hundred feet out of the slope of Mount Misery by a volcanic action which had all but lacked the strength to blow the projectile clear of the land. It was the beginning of a new volcano, but the action had stopped with the forcing up of the mass of rock which now forms Brimstone Hill. On the top of the rock is Fort George, one of the most fascinating masses of semi-ruin I have ever seen. With the atmosphere of the place still clinging to me I had read Colonel Stuart's "Reminiscences of a Soldier." He had spoken of Bedlam Barracks through which I had just been wandering, in his first letter to England. "Bedlam Barracks, Brimstone Hill, Mount Misery," he said, "are not the most taking of cognomens, but what's in a name?"

Until recent years there stood on Brimstone Hill the famous bronze cannon which bore the inscription :

"Ram me well and load me tight, I'll send a ball to Statia's Height."The wind freshened and St. Kitts with its Mount Misery and Brimstone Hill was rapidly slipping by as I passed into the shoal channel where "Old Statia" stood up seven miles away. The channel was "easy" on this day and I could give myself up to that altogether delightful contemplation of the approaching island. Characteristic from the east and west in her similarity to the two-peaked back of a camel, Statia is more striking when approached from the south where the Atlantic on its way to the Caribbean has cut into the slope of the "Quille," exposing the chalky cliff known as the White Wall. Blue, snow-shadowed, the White Wall gives an impression of freshness that seemed to belie the weathered battery which I could begin to make out at its western end. Here, during the calms of the hurricane season, the sperm whale comes to rub his belly and flukes against the foot of the cliff where it descends into the blue waters of the channel, to scour away a year's growth of barnacles.

Farther to the westward, de Windt's battery took form, while a thatched negro hut or two on the lower slopes of the "Quille" were the only evidence of human habitation. Behind it all, the perfect crater of the "Quille" rose, covered with an almost impenetrable tropic verdure which had flowed up the sides and poured into the bowl as the rain, from the time of the last eruption, had changed the volcanic dust into a moist earth of almost pre-glacial fecundity.

We had hardly passed mid-channel, it seemed, when the wind, eddying around the south end of the island, swept the canoe with lifted sheets past the corner of Gallows Bay, and I found myself bobbing up and down in the swell off the Lower Town of Oranje. As I lowered my rig and made snug, I could see below me, through the clear waters, what had once been a busy quay. The long ground swell dropping away from under threatened to wreck the centerboard of the Yakaboo on the ruined wall of a warehouse that had once helped to determine the success of the American colonies. On shore, an excited group of negro fishermen had gathered from the shadows of the broken walls to join the harbormaster who had lumbered from his hot kantoor (office) to the still hotter sands, in shirt and trousers -- and not without an oath.

"Watch de sea!" he yelled as half a dozen negroes waded in up to their waists."Look shyarp ! -- NOW!" and I ran the surf, dropping overboard into the soapy foam while the canoe continued on her course riding the shoulders of the natives to a safe harbor in the custom house.

"Oi see you floy de Yonkee flag," he said in greeting as I came dripping ashore, more like a shipwrecked sailor than a traveler in out-of-way places.

"Yes. My papers are in the canoe. "No hurry," he returned, "the first thing we do here, is to have a glass of rum -- it is good in the tropics.

And so I was welcomed to Statia, in the same open manner that the Dutch had welcomed and traded for centuries, and by the last of a long line of them -- one of the old de Geneste family.

While we were drinking our rum, the harbormaster seemed to suddenly remember something. Pulling me to the window, he pointed up to the ramparts of Fort Oranje hanging over us.

"You know de story of de salute ? --No ? --Well, I'll carry you to de Gesaghebber (governor) an' to de Fort an' we'll find de Doctor-HE can tell you better than I --but you can't go this way."Nor could I, for I had no coat but the heavy dogskin sea jacket, chewed and salt begrimed and altogether too hot for the oven-heat on shore. My shirt of thin flannel, once a light cream color, was now greased from whale oil and smoke stained from many a fire of rain-soaked wood. A hole in the back exposed a dark patch of skin, burned and reburned by the sun. My trousers were worn thin throughout their most vital area, the legs hanging like sections of stove pipe, stiff and shrunken well above my ankles with lines of rime showing where the last seas had swept and left their high water mark. My feet were bare, tanned to a deep coffee from continual exposure to the sun in the cockpit.

The third article of my attire and the most respectable was my felt hat, stiff as to brim from the pelting of salt spray and misshapen as to crown from the constant presence of wet leaves and handkerchiefs inside. The world may ridicule one's clothing and figure, but one's hat and dog had best be left alone. Still I cannot say that I was ill at ease or embarrassed for I was entirely in keeping with my surroundings. Marse James' office was neat and clean to be sure, but outside, up and down the beach there was nothing but ruin and heart-sinking neglect.

A razor, honed on the light pith of the cabbage palm, and a tin basin of fresh water contributed largely to the transformation which followed. Shoes and stockings from the hold of the canoe added their touch of respectability. It is remarkable what an elevating effect is produced by a mere quarter of an inch of sole leather. A neat blue coat and trousers borrowed from the harbormaster changed this cannibal attire to that of civilization. True, there was some discrepancy between our respective waist measures, but this was taken care of by a judicious reef in the rear and since it is hardly polite to turn one's back on a governor there would be nothing to offend this august official. With the coat buttoned close under my chin so as to show the edge of a standing military collar there would be nothing to betray the absence of white linen beneath.

They say that once upon a time the dignity of the Gesaghebber, whose authority extends over an area of scarcely eight square miles, was sorely tried by one of his own countrymen. An eminent scientist who came to investigate the geologic formation of the island, landed with much pomp and circumstance, wearing a frock coat and a silk hat. His degeneracy, however, was as the downward course of a toboggan, for only a few weeks later, upon his departure, he dropped in to bid the governor good-bye, attired in pajamas, slippers and a straw hat and smoking a long pipe that rested on the comfortable rotundity which was all the more accentuated by his thin attire.

I combed my hair and with my papers stuffed in my pockets set out to climb the famous Bay Path with the puffing de Geneste.

Built against the cliff which it mounts to the plateau above in a zigzag of two flights, the Bay Path belies its name. It is in fact a substantial cobbled roadway with massive retaining walls run up to a bulwark breast high to keep the skidding gun carriages of the early days from falling upon the houses below. That it had been built to stand for all time was evident, but even as I climbed it for the first time I could see that its years were numbered. The insidious trickling of water from tropical rains had been eating the soft earth away from its foundations and making the work easy for the roaring cloud bursts which take their toll from the Upper Town. The bulwarks that had comforted the unsteady steps of the belated burgher were now broken out in places and as we passed under the Dominican Mission the harbormaster drew my attention to the work of the last cloudburst which had bared the cliff to its very base. There was no busy stream of life up and down the wide roadway. As we stumbled up the uneven cobblestones we passed a lone negress shuffling silently in the shade of a huge bundle of clothes balanced on her head, down to the brackish pool where the washing of the town is done. Her passing only emphasized the forlorn loneliness of the hot middle day. We gained the streets of the Upper Town where the change from the simmering heat of the beach to the cool breezes of the plateau was like plunging into the cool catacombs from the July heat of Rome.

The Gesaghebber was still enjoying his siesta, we were informed by the negress who came to the door. In the crook of her arm she carried a sweating watermonkey from St. Martin's. She had addressed the harbormaster, but when she noticed that it was a stranger who stood by his side she dropped the monkey which broke on the flagging, trickling its cool water around our feet.

"O Lard -- who de mon?" she gasped."Him de mon in de boat," de Geneste mimicked -- for as such I had come to be known in the islands.

Leaving the servant to stare after us, we retraced our steps to the fort which we had passed at the head of the Bay Path. Saluting the shrunken Dutch sentry who stepped out from the shadow of the Port, we crossed over the little bridge which spans the shallow ditch and passed through to the "place d'armes" of Fort Oranje.

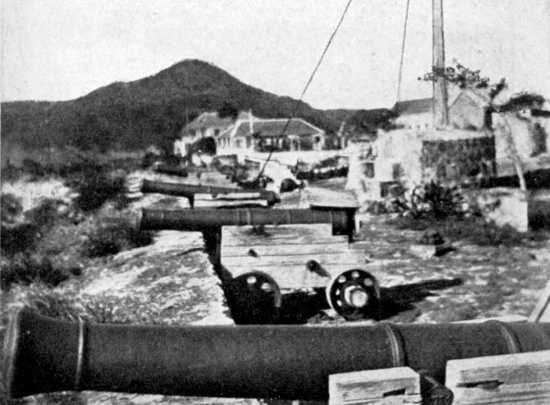

The old guns at Fort Oranje, St. Eustatius. The date 1780 may be seen on the trunnion of the nearest gun.

Forming the two seaward sides of an irregular quadrangle was the rampart, its guns with their hooded breeches pointing valiantly out over the roadstead and sweeping the approaches of the Bay Path. In the angle where the rampart turns back toward the town, stood the flagstaff, with topmast and cross trees, and stayed like a sloop, from which the red, white, and blue flag of Holland flapped in the trade wind. From just such a staff, held in that stepping before me, the Flag of Holland had been the first of a foreign power to dip in honor of the ensign of the infant navy of our Continental Congress. From this very rampart the first foreign salute had been delivered to our naval flag one hundred and thirty-five years before. Whether you will or not you must have a small bit of the history of Statia.

From her earliest days Statia belonged to the Dutch, who, before the British, were masters of the sea and for long years were supreme in maritime commerce. They have always been sailors as you shall see. The policy of the Dutch has always been for free trade and by this they became rich in the West Indies. Oranjetown, on the lee side of the island, half on the cliff, half on the beach, Upper and Lower Town as it was called, with its open roadstead where at times two hundred trading vessels have lain at anchor, possessed no advantages except those of free trade. Statia became a port of call. When our thirteen colonies broke away from the mother country the old Dutch Republic sympathized with the young one and the Dutch made money in the commerce that followed. When the struggle for independence broke out Statia was one channel through which the colonies procured munitions of war. Every nation has its blackguards and it seems that English traders at Statia actually supplied to the American colonists powder and cannon balls which were made in England and sent to them in Statia. This Rodney knew and he had for a long time kept a hungry eye on the rich stores of Oranjetown. If he ever took Statia his fortunes would be recouped and -- perhaps Marshall Biron knew this when he paid the debts of the old fighting roué and sent him back to London. It was on account of these English merchants -- "vipers" Rodney calls them -- that upon returning to the West Indies one of his first acts was to loot Statia. His most plausible excuse, however, was because here at Port Oranje, on the cliff above the bay, the first foreign recognition was made of our naval flag. You shall have the story "just now, as they say in the islands.

It was on the 16th of November, 1776, that the brig Andrea Doria, fourteen guns, third of our infant navy of five vessels, under the command of Josiah Robins sailed into the open roadstead of St. Eustatius and dropped anchor almost under the guns of Fort Oranje. She could have borne no more fitting name than that of the famous townsman of Columbus, who, after driving the French out of his own country in 1528, founded the republic of Genoa and with the true spirit of democracy, refused the highest office of the grateful government which he had established. The Andrea Doria may have attracted but little attention as she appeared in the offing, for in those days the two miles of roadstead from Gallows Bay to Interloper's Point were often filled with ships. But with the quick eyes of seafarers the guests of Howard's Tavern had probably, even as she was picking out her berth, left their rum for the moment to have their first glimpse of a strange flag which they all knew must be that of the new republic.

Abraham Ravené, commandant of the fort, lowered the red, white, and blue flag of Holland in recognition of the American ship. In return, the Andrea Doria fired a salute. This put the commandant in a quandary. Anchored not far from the Andrea Doria, was a British ship. The enmity of the British for Holland and especially against Statia was no secret. In order to shift the responsibility, Ravené went to consult Johannes de Graeff, the governor, who was at that time living in the hills at Concordia, his country seat. De Graeff had already seen the Andrea Doria, for Ravené met him in the streets of the Upper Town. A clever lawyer and a keen business man, the governor had already made up his mind when Ravené spoke. "Two guns less than the national salute," was the order. And so we were for the first time recognized as a nation by this salute of eleven guns. For this act, de Graeff was subsequently recalled to Holland, but he was reinstated as Governor of Statia and held that position when the island was taken by Rodney in 1781. The Dutch made no apology to England. Two years after this salute of '76, John Paul Jones was not served so well at Quiberon, for the French gave him only nine guns, the number at that time accorded to republics. This, of Statia, may well stand as our first naval salute.

Near the flag stepping was a bronze sundial mounted on a base of carved stone, its creeping shadow marking off the long listless days of the stagnant island as it had measured the too short hours of the busy port. It was like the tick of a colonial clock in the abode of the spinster remnant of a once powerful family. As I stood on the edge of the rampart and looked down on what was left of the Lower Town, it was hard to realize that the ruined walls below us had once held fortunes in merchandise and that in the empty Road before me had ridden ships captained by the same hard shrewd Yankee skippers that we still know on our own coast -- skippers as familiar with the bay and the rum shops of Oranjetown as their own neat little gardens at home.

Forming the two inshore sides of the quadrangle was a row of one-storied buildings, pierced near one end by the vaulted Port through which we had entered. The largest of these, a few steps above the southern end of the rampart, was built of stone. Here in the very room that Ravené had used as Commandant of the island, I gave my papers to the present officer. He was a new arrival from the Old Country and as yet knew no other language than the crackling speech of Holland. As he took the papers, he stepped to the window and his superior smile vanished when he saw that there was no boat lying in the Road. Mars James came to my rescue in the unintelligible fusillade that followed. While the harbormaster unsnarled the tangle of red tape, I improved the opportunity to look about me. In his report of the military defenses of the island in 1778, Ravené describes the building as a stone structure having two rooms ; the first a sort of council chamber and the second a gun room. The latter still contained the old gun racks which held the modern descendants of the old snaphaanen. He also mentions the barred cellar beneath, which was used as the criminal and civil prison. Some days afterward, while poking about in its musty depths, I found some of the old flintlocks and a pile of grape shot, rusted to a depth of a quarter of an inch, like those which Statia furnished to the needy army of Washington. There was still use for a jail, I found, for in one of the wooden shanties of that tumbledown row a negress was confined awaiting transportation to the penitentiary at Curaçao. She had an incurable mania for theft.

My papers duly viséd for Saba, we again made our way to the Gesaghebber. We found him, very much awake this time, in an animated discussion over a horse trade with the Medical Officer. "Frigid little lump of ice!" I muttered to myself at the curt nod he gave me. The Doctor was another sort. A Welshman by birth, an American by education, and a sailor by nature, I found that he had traveled widely and we were soon so deep in conversation that the pompous little governor, who knew no English, was forgotten for the moment. The harbormaster and the horse trade slipped away unnoticed. Another horse galloped in, the hobby of the Doctor.

"Did you know that the original cannon used in the first salute to your flag are still lying in the sand where they have been thrown down from the ramparts of the fort?"I feigned ignorance, thus removing a dam which might have held back some of those interesting bits which so often drift out on the stream of a story, unimportant perhaps in itself. Next to the art of sitting on a log, the ability to listen well is one of the crafts of life in the open. And then, as a diamond, in the vast sheet of blue mud which flows over the sorting tables of the Kimberley mines, is caught on the oily surface, a new name was spoken, that of a hero. Although I have since spent many hours in search of it, I have not found it in print. Krull -- a name which goes well with kruit (powder) and cannon, -Krull-Krut-Kah-non -- the gallant Dutch Admiral who fell in one of the most heroic sea fights of his time.

Rodney, upon the capture of Statia, learned that a convoy of vessels had left the island shortly before his arrival. They were under the protection of a lone Dutch man-of-war in command of Admiral Krull. In a letter of February 4th, 1781, to Phillip Stephens, Esq., Secretary to the Admiralty, he says:

"A Dutch Convoy, consisting of 30 sail of Merchant Ships richly loaded, having sailed from St. Eustatius, under the protection of a 60 gun ship, about Thirty-six Hours before my arrival, I detached Captains Reynolds [later Lord Ducie] of His Majestie's ship Monarch, with the Panther and the Sybil, to pursue them as far as the Latitude of Bermudas, should they not intercept them before he got that length."The slow-sailing convoy was caught and Krull commanded the ships to hold their course while he waited to stand off the three English men-of-war. He was killed in the unequal fight that followed. Lord Rodney says:

Since my letter of the 4th instant, by the Diligence and Activity of Capt. Reynolds, I have the Pleasure to inform you that the Dutch Convoy which sailed from St. Eustatius before my arrival have been intercepted. I am sorry to acquaint their Lordships that the Dutch Admiral was killed in the action. Inclosed, I have the honour to send Captain Reynold's letter; and am, etc."In a letter of February 10th, he says:

"The Admiral, who was killed in the action with the Monarch, has been buried with every Honour of War."In spite of this anger against St. Eustatius and the Dutch, Rodney had only admiration for the brave Krull.

We made our excuses to the governor and were soon scrambling among the ruins of the Upper Town. A fascinating mixture of old-world houses, surrounded by high walls which gave the streets the appearance of diked canals, of ruins and of negro shanties palsied by the depredations of millions of ants, Upper Oranjetown bore a character quite distinct from any of the West Indian towns of the lower islands. Here was no trace of a preceding French régime to give the houses uncomfortable familiarity with the streets and breed suspicion by their single entrances, nor did the everlasting palm thrust its inquiring trunk over the garden walls like the neck of a giraffe to inform the humbler plants within what was going on in the street. It lacked the moss-stained and yellow-washed picturesqueness of Fort de France and St. George's and for that very reason the novelty of it was restful. Above all was the feeling that here at one time had existed the neat thrift of the Dutch. With thrift comes money and with money comes the Jew. One wonders how the Jew with his feline dread of the sea, first came to Statia, knowing the long boisterous passage of those days. The reason may very properly have been the excellent seamanship of the Dutch traders. In the early history of Cayenne we are led to believe that the "fifteen or twenty families of Jews" were brought over by the Dutch. The Jew brings with him his religion and so we find the ruins of a one time rich little synagogue in one of the modest side streets. Whereas the Jew brings his religion with him as part of his life, the Christian brings it after him as part of his conscience. Thus we find, not far off, the tower of the Reformed Church with its unroofed walls. The Dutch "Deformed" Church as they have called it ever since a hurricane swept the Upper Town. In the shadows of the walls the Doctor showed me a long line of vaults where lie the old families, de Windts, Heyligers, Van Mussendens and last, the almost forgotten tomb of Krull, with no mark to proclaim his bravery to the world, and what need, for the world does not pass here -- the dead sleep in their own company in a miasm that seems to come up out of the ground and permeate the very atmosphere of the island.

As in Fort de France, I became a part of the life of Statia ; here was a place where I could live for a time. In six hours I had boon companions. There was the Doctor -- he would always come first and there was that inimitable Dutchman, Van Musschenbroek of Hendrick Swaardecroonstrasse, the Hague, who had an income and was living in a large house in the town which rented at $8.00 the month and was doing -- God knows what. His English was infinitely worse than my German and it was through this common medium that we conversed -- Dutch was utterly beyond my ken.

He used to come of a morning in his pajamas, hatted and with a towel on his arm and wake me for our daily bath. In that delicious fresh morning which follows the cool nights of the outer Antilles we three would scramble down to the Bay, the Doctor pumping the lore of the island into my right ear, the Dutchman rattling of outdoor expedients into my left. He, the Dutchman, was a well-built man, barrel-chested and with a layer of swimmer's fat, for he had once been the champion backstroke of Holland and a skater, and had geologized all over the world.

But we'll listen to the Doctor. Our favorite walk was to Gallows Bay, where there was a clean sand beach. We walked in a past that one could almost touch. As we took up the Bay Path, that first morning, just below the fort where a sweet smelling grove of manchioneel trees, tempting as the mangosteen of the Malays and caustic as molten lead, made dusk of the morning light, the Doctor touched my arm. There in a shallow pit, two yards from our path, lay seven rusty cannon, half buried in the sand. He did not have to tell me that these were the last of the old battery of eleven which had belched forth their welcome to the Andrea Doria. Some time after the salute, the guns were condemned and piled up near the present Government Post-Office in the fort where they remained till the late seventies. At that time an American schooner, cruising about for scrap iron, came to Statia to buy old cannon. The trunnions were knocked off so that they would roll the easier and they were thrown over the edge of the cliff.

The tomb of Admiral Krull.

Iron cannon, as a rule, bore the date of their casting on the ends of their trunnions whereas the bronze guns were dated near the breech. These bore no date, but they must have been old at the time of the salute. The schooner took four of them, but did not return for the rest. So these seven have remained as unmarked and unnoticed as the silent grave of Krull on the plateau above.

Farther along, on our way to the beach, was an immense indigo tank with its story. In the ken of the last generation, a ship had been driven ashore in a southwester, the tail of a hurricane. Most of the crew perished in the sea, but three came safely through the surf when Fate decided that after all they must join their comrades on the other shore. They clambered up the broken walls only to fall into the disused tank, now filled with brackish water, where they drowned like rats in a cistern.

Passing the walls of the last sugar refinery in operation on the island, we came to the beach. A blue spot in the sand caught my eye and I picked up a slave trading bead of the old days. It had been part of a cargo of a ship bound for Africa; her hulk lay somewhere out there in the darker waters of Crook's reef where it had lain for the last century or more, sending its mute messages ashore with each southwest gale, ground dull on their slow journey over the bottom of the Caribbean

The Bay was only habitable during the early morning hours, before the sun got well over the cliff above. The rest of the day I spent on the plateau where the sun's heat was tempered by the trade which blew half a gale through the valley between the humps, a fresh sea wind. The active men of Statia go to sea; there is little agriculture besides the few acres of cotton and sisal that cry for the labor of picking and cutting for here the negro is unutterably lazy.

I used to see from time to time a ragged old native; whose entire day was spent sitting in a shady corner, blinking in the sunlight like a mud-plastered turtle, dried-caked. Some one must have fed him, but I can assure you that this was not done from sunrise to sundown and he must have gone somewhere to sleep but during the light of day I never saw him stir. I passed him for the sixth time one day -- I wondered what was going on in the pulp of that brain pan; not conscious thought I was certain -- when a man hailed me from the doorstep of what was once a prosperous burgher's house -- a last white descendant of that very burgher. The excuse was a bottle of Danish beer but I read through that -- he wanted a breath of the outside world and I gave him what I had. He was not a poor white -- just another like de Geneste, left by an honorable old family to finish their book -- their last page. He lived with a negress whom he extolled and not altogether in self-defense. They were married and I took his word for it. She was cooking and washing in the kitchen when I came in and at the call of her master brought the beer and glasses on a tray with a peculiar grace mixed with an air of wifely right -- there was no defiance in her bearing but there was that which I might best describe as an African comme il faut. There was no attempt at an introduction and she left us immediately to resume her labors. We sat on a broken sofa -- they wear out and break down in Statia exactly as they do in some of the houses we know where first cost is the only cost -- but here they never go to the woodshed. I happened to glance through an open doorway into what was once a drawing room and there, reared up like a rocking horse about to charge forward from its hind legs, was a barber's chair.

"What in the name of Sin have you got that in there for?""Oh, oy cuts hair," he answered with that soft weatherworn tone that belongs to Statia alone. Whether this hair cutting was a partial means of livelihood or merely a pastime for the accommodation of his friends I did not ask. I was not even inquisitive enough to ask how the thing came to the island. My host asked me if I would like to have my hair trimmed and I said that I should be delighted. It was like accepting another bottle of beer. I adjusted my bones to the cadaverous red upholstery that showed its stuffing while my friend tied the apron around my neck. He did no worse than many a country barber I have met and with less danger from showerings of tonics and laying on of salves. Instead of fetid breathings of Religion, Politics and League Baseball, I listened to tales of old Statia. Some time when I am dining out and find an old Statia name beside me -- there are many in our eastern cities -- I may be tempted to say, "Gracious! are you a de ----? I have had the pleasure of a haircut in your great grandfather's drawing room."

It was while I was in the barber's chair that I was a witness to a scene that many times since has made me stop whatever I have been doing -- and think a bit. A sloop was lying in the roadstead bound that evening for Porto Rico. One of her passengers-to-be was the colored son of this man, who would seek his fortune in the more prosperous American island. The boy had been about town for a last palaver with his friends and now, in the late afternoon, had come to his home to say good-bye. He had already seen his mother and now came in where his father was cutting my hair. Oh, the irony of that parting! The boy showed little concern -- he was perhaps eighteen and dressed in store clothes of Yankee cut. It was the poor miserable father who was hurt -- a white man breaking down over the parting with his rather indifferent colored offspring. My friend excused himself to me and then putting his arms around the boy's neck sobbed his farewell on the boy's shoulder. His was a figure equal to the mad woman of St. Pierre, to his last shred paternal. I could say more but this is enough; may I be forgiven this intimate picture.

One morning the town awoke to find that a Dutch man-of-war was lying in the Roads and then Statia came to life for two days. The ship was the Utrecht, an armored cruiser stationed in the West Indies. In the late afternoon the ship's band climbed the Bay Path to the fort where I listened to the concert and struck up an acquaintance with a Russian captain of marines who cared not a whit for the beauties of the dying day and cursed the sun for his everlasting smile and prayed for a day of the grey weather of the Baltic. To tell the truth I was coming to it myself. The next morning I saw him at play with his clumsy Dutch marines -- they were having landing drill and a more cloddish lot I have never seen. They landed in three feet of water, mostly on all fours, from the gunwales of the ship's boats and one fellow -- I stood and watched him do it -- actually managed to sprawl under the boat and break his arm.

"Here was a town walled in by Nature."

The grand event of the Utrecht's visit, however, was on the night of the second day when a dance was given in the governor's house in honor of Her Majesty's officers. Before the dance a select few of us were invited to tea at the house of Mynheer Grube, the former governor. I accepted the invitation, borrowed some clean "whites" from the Doctor, combed and brushed my hair, and went.

There was something very placid and restful about this home of the old Dutch gentleman and his wife -- the quiet dignity of a useful life frugally lived and of duties conscientiously performed. There were old clocks and cupboards in it and a Delft plate or two just as we find them in our Dutch colonial houses of the north. If you examine the outer walls carefully you will find a round place, plastered up as though at some time a cannon ball must have gone through. One did and it was not many generations ago when just such a quiet Hollander as Grube was living there as Governor.

It was some time after the looting of Oranjetown, when Statia had been sucked dry by the English and flung back to the Dutch like a gleaned bone, that a French frigate in passing fired upon the Upper Town just to see the mortar fly. It was in the trade season and she bowled along, close under the lee of the island with her weather side exposed as if to say, "Hit me if you can."

One of her shots passed through the very room in which the governor sat reading. His wife, -- I wonder if she had been in the kitchen overlooking the making of some favorite dish ? -- rushed into the room and found her husband calmly reading with the debris of stone and plaster littered about him, as though nothing had happened. She begged her husband in the name of all that was sane to move from his dangerous position.

"Be calm," said the governor, "don't you know that cannon balls never strike again in the same place?"But he was not altogether right. Down on the beach, just beyond Interloper's Point, lay the little old battery of Tommelendyk -- Tumbledown-Dick they call it. There had been but little use for the guns of late and there was no militaire now stationed on the island. There was, however, one man on Statia, a one-armed gunner whose blood was roused when he saw the wanton firing of the Frenchman. He was working in his field, not far from Tommelendyk and he remembered that there was still some powder and shot left in the magazine and that one of the guns at least was in good order for signaling purposes. He rushed down to the battery followed by his friends.

In a twinkling the breech-hood was off and the gunner blew through the touch-hole to make sure that the passage was clear. Measuring the powder by the handful, he showed his friends how to ram home the charge and the ball. By this time the Frenchman was almost abreast the battery. The gunner's first shot was a good "liner," but fell short. He had not lost his cunning in guessing the speed of a ship. The impromptu crew reloaded in quick time and as they jumped clear of the smoke they gave a yell of delight. The shot had struck the Frenchman in the hull close to the waterline. Two more shots were planted almost in the same place before the frigate could clear the island.

When she ran into the choppy seas her crew found that their ship was rapidly making water. They dared not beat to windward to St. Martin's and were forced to make for St. Thomas, the nearest port to leeward. With her guns and stores shifted to port she must have been a weird spectacle as she bore down on the Danish island, with a free wind and heeled as though she were beating into a gale.

Grube had been Governor in the same way that his predecessors had held office -- burghers performing their duty to the state without political influence and by right of a worthy life. We had our tea and cakes and drank our Curaçao in the short evening that brought with it the last music of the band at the fort. Then we arose and went to the house of the present Governor where most of the white people of Statia were already gathered as one huge family. The room was on the upper floor -- there are never more than two in these islands -- to which we gained access by an outside stairway, from the courtyard, a most convenient arrangement by which a large crowd of guests could not invade the privacy of the rest of the house. Most of the officers of the Utrecht were there and the midshipmen -- young boys such as you might meet at almost any dance in Edgewater or Brookline.

It had been a long time since I had danced and I reveled in this party of the Governor of Statia. I danced with Heyligers and de Windts and Van Mussendens and no end of names that had been in the island long before the coming of Rodney. I danced with names and my spirit was in the past. The tunes they played were old ones, some of them English and some handed down from the time when the Marquis de Bouillé made the island French for a year. There were quaint French themes, some of which I recognized. To these same tunes, in this same room, the ancestors of these people had danced many a time. Then the orchestra switched to more modern things -- "Money Musk" and the old sailor's delight "Champagne Charlie" which you will only hear in our parts in some wharfside saloon, befuddled through the lips of some old rum laden shellback. But withal this ancient atmosphere and the dire poverty of these descendants of once prosperous burgher families there was no sadness at the Governor's that night. If these people were always talking of the glorious Past their introspection had not made them morbid. They were seafarers and their philosophy was a hopeful one. Here was the gathering of a congenial happy family. I have never dropped into a community where I felt so immediately and completely at home as here and at Saba. There is one word which applies to these people more than any other and that is -- Good-hearted. They are not super-educated surely but they have a far wider knowledge of the world in general than our average farmer community. They retain a refinement of family which generations of poverty have not been able to down and they have survived the fires of want with a spirit that is one of the paradoxes of the world.

The orchestra finally reached the limit of its strength and stopped playing through sheer exhaustion -- they were not professionals, just friends who were glad to do this service. From time to time one of the players would lay aside his instrument and join the dancers for a while till by rote each had had his share. The ending of the music seemed to be the accepted signal for refreshments and those who did not take up trays of coffee and small cakes lined up along the walls as before the dance. The coffee had an awakening effect but the dance did not continue. Presently a whisper found its way from mouth to ear till it reached Van Musschenbroek in a far corner. His perspiring face smiled assent and he stepped into the middle of the cleared room. In laughable broken English he announced that he would now delight the audience with an imitation of a fiddler crab. It was a clever stunt and from the way in which he skittered about the floor in arcs of wandering centers weaving his claws in the air, I knew that he knew beach life. And so the second part of the evening was started. There was no assumed modesty that needed coaxing -- whoever was asked deemed it a pleasure to do his part of the entertaining ; was this not a way in which he might honor the Governor and his wife? The midshipmen of the Utrecht entered into the spirit of the thing and one of them sang a Dutch song. Most of these chaps had been on the Utrecht when she attended the Hudson-Fulton celebration in New York and for a time we had a bit of Keith's circuit on the boards. George M. Cohan did not sound a whit better than when we hear him imitated at home. There is a limit to all good things and these people live in moderation and never reach the limit -- the party broke up when we were all happily tired.

I became attached to Statia as I had become attached to Point Espagñol and Fort de France, but I found that little by little my eyes sought the sea more and more. The channel was calling again and peaked Saba became a aggravating invitation. With all the fascination of the old fort and the batteries, the stories of the privateers and the brisk companionship of the Doctor, the call was stronger than the present love, and so one morning I took to the shimmering channel and left the island of England's wrath for her sister where the Dutch rule the English.