Hurricane Mitch- Synopsis The Origins

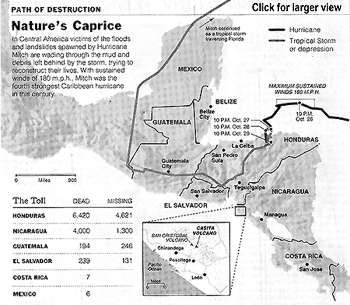

The Origins In West Africa, A Storm Is Born In the second week of October, an unremarkable atmospheric disturbance, accompanied by thunderstorms, moved west out of Africa and into the Atlantic Ocean. A hundred or so of these tropical waves, as meteorologists call them, do the same every summer and fall. For a week the tropical wave that would become a hurricane raised few alarms as it crossed the ocean, eventually reaching the eastern Caribbean, near the Lesser Antilles, on Oct. 19. Nine out of 10 of these waves eventually dissolve. "We see thunderstorms every day," said John Guiney, a hurricane specialist at the National Hurricane Center in Miami. "The key thing is persistence." But this disturbance did persist, and it grew stronger as it moved into the warm waters of the. central Caribbean, where sea-surface temperatures are well above the 80-degree mark necessary to generate a hurricane. During the next two days, it sucked up moisture and heat and its winds began to rise. On Oct. 21 meteorologists at the Miami center determined that the pinwheel-shaped storm had become a tropical depression, as baby hurricanes are known, and they dubbed it Mitch, in accordance with their alphabetical list. It was 360 miles due south of Jamaica, moving north. By the next afternoon, the hurricane's winds had risen to 45 miles an hour, and it was classified a tropical storm. But it still offered no clue to United States Air Force scientists who flew over it in a specially outfitted C-130 cargo plane of what it would become. "There really wasn't much of a center," said Maj. Rich Harter, a meteorologist on board. The night of Oct. 22 and through the next day, everything changed. The storm exploded in ferocity. By Oct. 24 it was a full-blown hurricane with 90-mile-an-hour winds, about 200 miles south-southwest of Jamaica and inching north at seven m.p.h. Though the storm was far out at sea, torrential rains hit Costa Rica, where floods killed seven. Cuba and Jamaica began preparing for the impact, but on Oct. 25 the storm veered westward and ambled menacingly toward the Yucatan Peninsula. People in Belize and Mexico braced for the worst. Dozens of foreign journalists traveled to the resort city of Cancun, Mexico, to Cover the storm.

By Monday, Oct. 26, the hurricane had became a true monster, with winds of 180 miles an hour, moving west. Although the eye of the storm was 100 miles north of the Honduran coast, heavy rains began falling across Central America. The barometric pressure at the center - a standard measure of intensity - fell to 905 millibars, tying it with Camille in 1969 for the fourth-strongest Atlantic hurricane oh record. To meteorologists it was beautiful, a true marvel of nature. The Air Force reservists who flew into it, members of a crew based in Biloxi, Miss, called the Hurricane Hunters, saw the Stadium Effect: a perfect bowl-shaped mass of clouds around a clear center, with circular tiers like a football arena. "We were all in awe," said Mr. Guiney, in Miami. "This was the atmosphere at its worst in terms of its impact on man." Landfall Honduran Island Takes the Brunt Then nature's caprice intervened once more, in the form of a high pressure system north of the hurricane. Those east-west winds deflected the hurricane and steered it west before slackening and leaving the storm drifting aimlessly off the Honduran coast, often hovering over one spot in the ocean, churning up cold water from deeper in the sea and thus weakening the storm. The residents of a Honduran island, Guanaja, had to take cover on the afternoon of Monday, Oct. 26. They spent a hellish three days. "For me it wasn't a hurricane - it was a typhoon," recalled Edward Cooper, a launch captain who rode out the storm hiding in a cistern behind his house. "It was here for three days, hitting us."

Vacationers at the resort at Posada del Sol described days of listening to a shrieking wind outside their cement compound, like a freight train or jet engine. Many of the island's 5000 residents waited out the storm in a protected cove. Luis Pagoada, 48, a land surveyor, weathered the storm with 12 other people inside a trawler pulled up on a beach behind a seawall. Although the group had food and water, he said, they nearly lost their composure by the third day of screaming winds and high surf pounding the wall. "We didn't know if the sea was going to bury us," he said. The hurricane destroyed most houses on the island, tore boats from their docks and knocked out all power and telephones. Flowers and greenery were blown away, leaving a barren landscape, with only tree trunks protruding from denuded hills, Mr. Pagoada said. Six people were killed. "It was just luck, luck, simple luck that I survived," he said. At a nearby mainland town, Santa Rosa de Aguan, a teacher, Laura Isabel Arriola de Guity, reportedly drifted on a makeshift raft in The Caribbean for six days before her rescue. Her husband and three children died. On the Mainland Fierce Rains Bring Floods and Death The next day, Thursday, Oct. 29, the hurricane hit the hilly north coast of Honduras, near Trujillo. Its winds slackened to 60 miles an hour, downgrading it to a routine tropical storm. But it produced enormous downpours, and Major Harter, of the Hurricane Hunters, said flying through the storm at that point "was like being in a shaky car wash for about six hours." As it wandered across Honduras during the next 48 hours, the storm dumped as much as two feet of rain in some locations, according to unofficial estimates. The rivers and creeks lacing Honduras's mountainous countryside quickly swelled to several times their normal size, flooding entire towns. In the north, the floods destroyed vast banana plantations belonging to American companies and damaged coffee crops. Countless families were stranded on rooftops, surrounded by water. Countless others drowned as they struggled to find higher ground. Communications were knocked out. In the central region, the rain began failing in earnest on Thursday afternoon and did not stop for three days. As the rivers rose rapidly, the Government began issuing warnings on radio and television to people living in river valleys and on steep slopes. By Friday afternoon, the Choluteca River had put many parts of Tegucigalpa, the capital, under water. Factories, hospitals, prisons and several neighborhoods were swept away, along with livestock and an unknown number of people. People living next to the river abandoned houses and sought shelter on higher ground. "Everything went by in the river," said Alejandro Isaguire, a 35-year old farm worker. "Cattle, cars, tires, buses, refrigerators. It was scary. It made me pray to God." The Mayor of the capital, Dr. Cesar Castellanos, visited several endangered neighborhoods in an effort to move people out. While some abandoned their houses, others resisted, fearing looters. "A lot of people lost their lives and property by not doing what they were told," said Norman Garcia, a local tobacco merchant. "The problem here was nobody saw the magnitude of water the storm was going to come with." Late Friday and in the early hours of Saturday, the true horrors began. Across Honduras, landslides and avalanches buried whole villages and destroyed dozens of poor neighborhoods in major cities, especially in the capital. Tomas Zelaya Gomez, 73, was asleep in his bed with his wife when his house was destroyed in a landslide that took the lives of at least 13 people, including his daughter and granddaughter. "I didn't hear the noise because I was sleeping," he said. "But when I woke, I felt that the walls were falling in. I grabbed my wife and we left our room and went into the corridor. There was this enormous crash." The couple made it out of the wreck, only to find most neighbors' houses had slid into a river below or collapsed in an avalanche. With the earth still moving under his feet, Mr. Zelaya tried desperately to pull relatives from the rubble. Fifteen minutes later there was another rumbling from the mountainside. The survivors fled just before a second landslide took everything left of the homes down into the river below. Some riverside communities, like Morolica in southern Honduras, were entirely washed away. The floods destroyed dozens of shrimp farms and melon plantations in the south. Scores of bridges were knocked out, along with power lines. But perhaps no place was harder hit than Casita Volcano, in northwestern Nicaragua, near the town of Posoltega and close to the border with Honduras. The incessant rains filled the volcano's crater with water, creating a lake. On Friday afternoon the crater's wall gave way, burying about 14 villages in mud and killing at least 1,500 people. "It is like a desert littered with buried bodies," said the Mayor of Posoltega, Felicita Zeledon. Still, news of the catastrophes was slow to reach the outside world. By Saturday morning, communications systems were crippled and all the major roads were impassable in Honduras and in much of Nicaragua. Landslides continued to occur around the country through Sunday. The Government's efforts to respond suffered another blow that afternoon when Mayor Castellanos, a popular politician who had a good chance to become the next President, was killed in a helicopter crash. He had been trying to travel to an outlying suburb to warn people about a possible mudslide. Besides, the storm was not yet finished. Unwinding and slowing down, Mitch moved west across Honduras on Saturday, then raked through Guatemala and El Salvador on Sunday, finally losing power that afternoon as it entered Mexico, near Tapachula. The Aftermath Towns and Cities Buried in Mud On Monday, as skies cleared somewhat, the scale of the disaster became apparent. "We have before us a panorama of death, desolation and ruin throughout the entire country," the Honduran President, Carlos Flores Facusse, told his stunned nation in an address that evening. La Ceiba, in the north, was flooded and cut off by downed bridges. San Pedro Sula, the economic hub, was under a meter of water and its airport was badly damaged. The road linking the capital to San Pedro Sula and the Caribbean port at Cortes was cut, as was the road from the capital to the Pacific Coast. Much of downtown Choluteca, the economic engine of the south, had been buried in mud. Government officials say Honduras has lost most of its coffee and banana crops, worth about $500 million, and about 70 percent of the year's grain harvest. "It's tragic what has happened to us," said Marco Polo Michiletti, the Deputy Minister for Agriculture. Throughout Central America, hundreds of towns found themselves cut off, unable to get shipments of food or medicine and without clean water. "We are completely incommunicado," said Juan Francisco Alvarez, Mayor of Soledad, when a Mexican helicopter arrived with a small shipment of food last week. His community lost 14 people. "Eighty percent of our roads are damaged," he said, wearily ticking off the town's woes. "All the bridges are out. There is no electricity. There are no telephones. We are rationing food." On Monday afternoon, the United States Air Force began search-and-rescue helicopter operations from Palmerola, about 30 miles northwest of the capital, plucking more than 670 people from roofs and trees during the next three days. More . than 600,000 homeless people were crammed into schools, churches and other temporary shelters. On Wednesday more help arrived. Mexico sent helicopters, cargo planes, troops trained in rescue missions and 700 tons of food. Japan pledged to repair two crucial bridges. The United States followed suit, pledging $70 million to help rebuild Honduras. On Saturday the United States stepped up its efforts, shipping in 30 tons of food along with bulldozers and a corps of about 1,000 Army engineers to help repair bridges. As the week wore on, Tegucigalpa grew tense. Prices rose and food disappeared rapidly from grocery shelves. Hundreds of cars lined up at gasoline stations, where armed guards kept order. The Government instituted a nighttime curfew and banned the drinking of alcohol to combat looting. Desperate people dug through, the muddy rubble of former stores, looking for canned goods. By Friday the main highway linking Tegucigalpa to Port Cortes was reopened after engineers, working 24 hours a day, filled in the gaping ravine left when water washed away a culvert. Trucks carrying fuel and food began reaching the capital. As the waters receded, more bodies were found. Firefighters recovered two that were found wedged under the wrecked Mallol Bridge in Tegucigalpa on Saturday evening, and another was discovered in the mud in the Rio del Hombre, about 10 miles from Tegucigalpa. Although the bodies of most of the 6,400 people the Government estimates were killed in Honduras may never be found, the hurricane appears to have been the Atlantic's deadliest in two centuries. In Tegucigalpa, only 20 bodies have been recovered. Hundreds have been reported missing, and are presumed dead. "A huge number of people are buried," said the city coroner, Dr. Lucy Marrder. "There are entire settlements that are buried and they haven't recovered the bodies." How to Help The Victims Of the Storm Many aid agencies are accepting contributions to help the Central American flood victims. Here are some of them:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||